AI and professional liability: what happens when the answer is wrong?

When AI-assisted tax research leads to wrong advice, Belgian law is clear: the professional pays. But that's actually the strongest argument for using transparent AI — not against it.

By Auryth Team

A Belgian tax advisor relies on an AI tool to research the current rate applicable to a client’s investment structure. The tool retrieves Art. 19bis WIB 92 — real article, real code — but serves the version from before the last programme law amended it. The advisor gives advice based on the outdated rate. The client acts on it. The tax assessment arrives. The damage is done.

Who pays?

Belgian law answers this question with zero ambiguity. The professional pays. Every time. Regardless of which tool produced the error.

The liability framework that already exists

Belgium doesn’t need new AI legislation to answer the liability question. Book 6 of the Belgian Civil Code — which entered into force on 1 January 2025 — provides the complete framework.

Art. 6.5 states that everyone is liable for damage caused by their fault. Art. 6.6 defines fault as either a violation of a specific statutory rule or a breach of the general duty of care (zorgvuldigheidsnorm). No distinction between an error you made manually and one you made by trusting a tool.

The standard is the normally careful and competent professional (normaal voorzichtig en bekwaam beroepsbeoefenaar) in the same circumstances. A tax advisor who relies on AI output without verification falls below this standard, just as one who relies on an outdated paper codex would.

One significant change in the new Book 6: Art. 6.3 abolishes the old prohibition on concurrent claims (samenloopverbod). A client harmed by wrong tax advice can now pursue both contractual and tortious remedies against the same advisor. This widens the advisor’s exposure surface.

The AI error epidemic nobody expected

The liability question isn’t hypothetical. Worldwide, 486 documented cases of AI hallucination errors have been identified in legal proceedings — 324 in US courts alone. Over 200 of these occurred in the first eight months of 2025 (Jones Walker, 2025).

The landmark case: Mata v. Avianca (SDNY, 2023). Attorneys submitted a legal brief containing six entirely fabricated case citations generated by ChatGPT. The cases didn’t exist. The judges cited didn’t write those opinions. The outcome: $5,000 in sanctions and a professional reputation destroyed.

But Mata v. Avianca was just the beginning. By mid-2025, three separate US federal courts sanctioned lawyers for AI-generated hallucinations in a single two-week period. Sanctions have reached $10,000 per incident.

The most alarming development: in September 2025, lawyers were sanctioned not for submitting AI-fabricated citations, but for failing to detect that opposing counsel’s citations were fake. The duty of verification is expanding.

The dependency trap

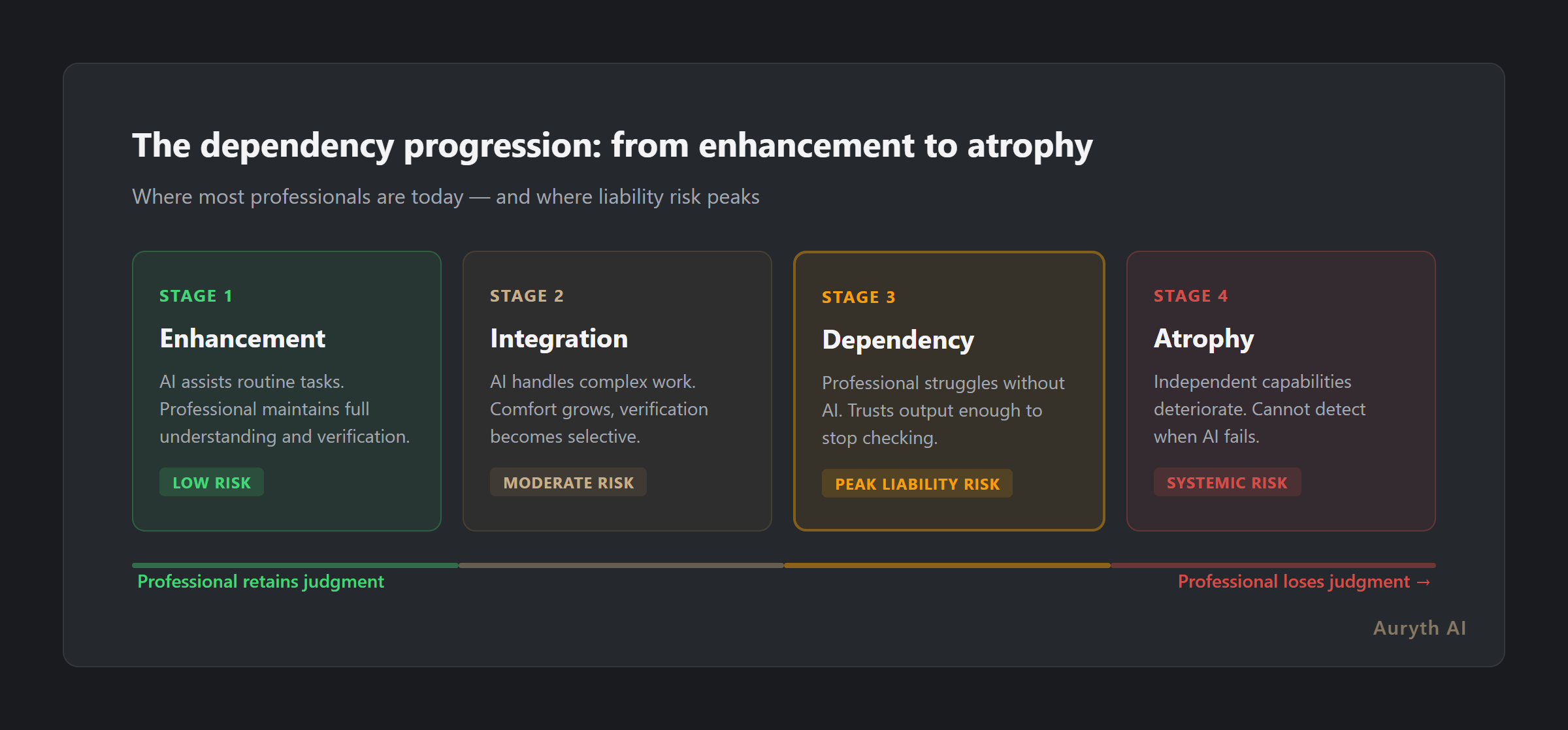

These cases reveal a pattern that goes beyond individual carelessness. Researchers have identified a four-stage dependency progression in how professionals adopt AI (Jones Walker, 2025):

- Enhancement — AI assists routine tasks; the professional maintains full understanding

- Integration — AI handles increasingly complex work as comfort grows

- Dependency — the professional struggles to work without AI

- Atrophy — independent practice capabilities deteriorate

Many knowledge workers have already reached stage 3. This is where liability risk peaks: the professional trusts AI enough to stop verifying, but hasn’t lost enough skill for anyone to notice — until something goes wrong.

The most dangerous phase of AI adoption is when the professional trusts the tool enough to stop checking, but not enough to understand when it fails.

What the EU requires — and what it doesn’t

The EU AI Act (Regulation 2024/1689) introduces AI literacy obligations (Art. 4, effective since 2 February 2025) and deployer obligations for high-risk AI systems (Art. 26, full compliance by 2 August 2027). Professionals using AI for tax research may qualify as “deployers” — which would require human oversight, monitoring, and record-keeping.

The revised Product Liability Directive (in force since 8 December 2024, transposition deadline 9 December 2026) now explicitly covers software, including AI systems. If an AI tool produces a defective output — serving outdated law, for example — the manufacturer could face strict liability. This creates a recourse path: the professional pays the client, then claims against the AI provider.

What the EU doesn’t have: a harmonised AI liability directive. The proposed AI Liability Directive was withdrawn in October 2025 after stakeholders couldn’t agree on causality presumptions. This means Belgian professionals fall back entirely on national tort law — Art. 6.5 and 6.6 of the Civil Code.

The contrarian argument: NOT using AI is becoming the risk

Most professionals frame AI as a liability risk. The more interesting question is whether the risk is shifting in the opposite direction.

The ABA’s Model Rule 1.1 (Comment 8, amended 2012) requires lawyers to “keep abreast of changes in the law and its practice, including the benefits and risks associated with relevant technology.” The ABA’s Formal Opinion 512 (July 2024) extended this explicitly to generative AI: lawyers must have “a reasonable understanding of the capabilities and limitations” of AI tools.

The pattern is familiar. When electronic legal databases became available — Jura, monKEY, Fisconetplus — no single court declared manual-only research negligent. But the standard shifted organically. Courts and peers came to expect database-assisted research as baseline competence. Today, a tax advisor who researches a complex cross-border question using only paper codes would be considered careless, not principled.

AI research tools are on the same trajectory. If a tool demonstrably catches legislative amendments faster than manual monitoring, can a professional who ignores it claim they met their duty of care?

| Approach | Liability argument |

|---|---|

| Uses AI without verification | Below standard of care — didn’t verify, trusted blindly |

| Uses AI with verification | Above standard of care — broader research, documented sources, audit trail |

| Doesn’t use AI at all | Today: defensible. Tomorrow: increasingly difficult to justify as the standard shifts |

The transparency argument

If professional liability persists regardless of the tool, the question isn’t whether to use AI — it’s which AI to trust.

An opaque AI tool (generic chatbot, no sources) gives the professional nothing to verify and nothing to cite. If the output is wrong, there’s no audit trail, no confidence signal, and no way to demonstrate due diligence.

A transparent AI tool (source citations, confidence scores, temporal versioning, authority ranking) gives the professional exactly what they need for a defensible workflow:

- Source citations link every answer to specific provisions, rulings, or commentary — verifiable in seconds

- Confidence scores signal when the system is uncertain — the professional knows where to double-check

- Version history shows which version of the law was applied — no silent application of outdated provisions

- Audit trails document what was searched, when, and what was found — evidence of due diligence

The paradox: the AI tool that admits uncertainty is safer than the one that sounds confident.

Practical framework: using AI defensibly

For Belgian tax professionals navigating this landscape, six principles:

- Verify every critical citation. AI accelerates research; it doesn’t replace verification. Check the article number, the version date, and whether the cited source actually supports the claim

- Document your process. Record which queries you ran, which sources the tool returned, and what verification steps you took. This is your evidence of due diligence

- Watch the confidence signals. When a tool flags uncertainty, treat that as a prompt for manual research — not as a reason to ignore the answer

- Understand the tool’s limitations. Know what corpus it covers, how frequently it updates, and what types of content it excludes. Art. 4 of the AI Act requires this literacy

- Maintain independent competence. The dependency progression is real. Periodically research without AI to keep your professional skills sharp

- Choose transparent tools. An AI tool without source citations is a liability — not an asset. If you can’t verify the output, you can’t defend the advice

Common questions

Does using AI shift professional liability to the AI provider?

No. Under Belgian tort law (Art. 6.5-6.6 BCC), the professional is liable for their own fault — including the fault of relying on unverified AI output. However, the professional may have recourse against the AI provider under contractual liability or the revised Product Liability Directive, depending on the circumstances.

Does Belgian law require professionals to disclose AI use to clients?

Not explicitly — yet. But the general duty of transparency and the deontological obligation of honesty suggest that material reliance on AI tools should be disclosed, especially when the AI’s output directly shapes the advice given. The ITAA has not yet issued specific guidance on this point.

Will insurance cover AI-related professional errors?

Unclear. Many professional indemnity policies have “silent AI” coverage — AI risks neither explicitly included nor excluded. Some international insurers have already introduced AI exclusions. The ITAA’s collective policy covers negligence broadly, but AI-specific claims haven’t been tested. This uncertainty is itself a reason to use verifiable AI tools that reduce error risk.

Related articles

- Why transparency matters more than accuracy in legal AI → /en/blog/transparantie-vs-nauwkeurigheid-en/

- What is confidence scoring — and why it’s more honest than a confident answer → /en/blog/confidence-scoring-uitgelegd-en/

- The EU AI Act and legal AI: what Belgian tax professionals actually need to know → /en/blog/eu-ai-act-juridische-ai-en/

How Auryth TX applies this

Auryth TX is designed for exactly this liability landscape. Every answer includes source citations linked to the specific provisions, rulings, or commentary that support it. Confidence scores signal when the retrieved sources weakly support the generated answer — so the professional knows when to verify more carefully.

The temporal versioning system tracks which version of each provision was applied, when it entered into force, and whether amendments have been published since. Saved research is flagged when underlying law changes. The full query history provides an audit trail that documents the professional’s research process.

We don’t eliminate liability — Belgian law doesn’t allow that, and it shouldn’t. We give professionals the transparency they need to demonstrate that they did their work carefully, verified their sources, and exercised the professional judgment that the law requires.

Sources: 1. Selbst, A.D. (2020). “Negligence and AI’s Human Users.” Boston University Law Review, 100, 1315-1376. 2. Buiten, M.C., de Streel, A. & Peitz, M. (2023). “The Law and Economics of AI Liability.” Computer Law & Security Review, 48. 3. Bertolini, A. & Episcopo, F. (2023). “The European AI Liability Directives — Critique of a Half-Hearted Approach and Lessons for the Future.” Computer Law & Security Review.