AI hallucinations: why ChatGPT fabricates sources (and how to spot it)

Why language models invent legal citations, what makes Belgian tax especially vulnerable, and three defenses that actually work.

By Auryth Team

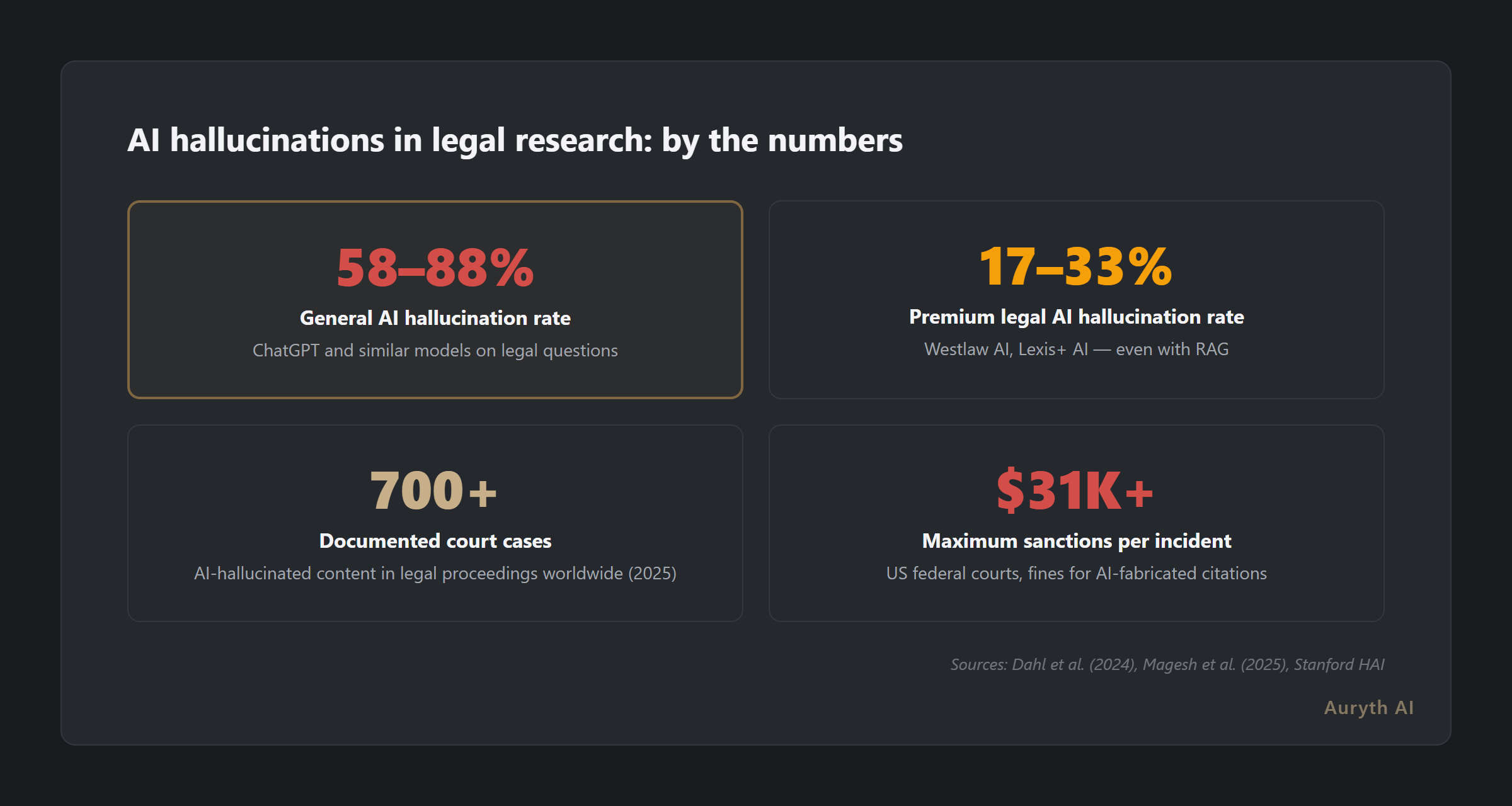

Stanford researchers tested the most expensive legal AI tools money can buy — Westlaw AI, Lexis+ AI — and found they fabricate information on 17–33% of queries. General-purpose models like ChatGPT? Between 58% and 88%.

Those numbers aren’t bugs on a roadmap. They’re features of systems that were never designed to distinguish legal fact from plausible fiction.

What is an AI hallucination?

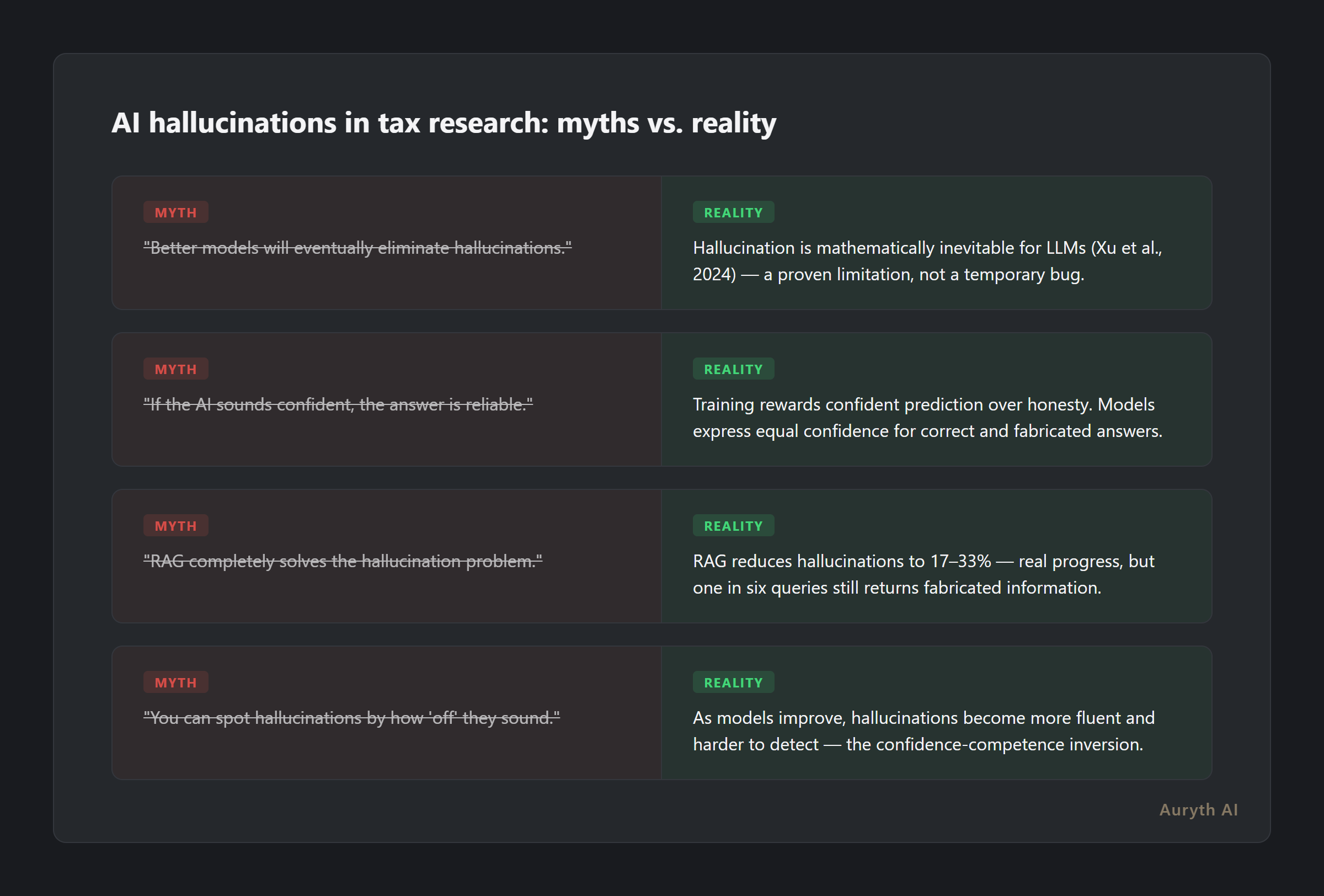

An AI hallucination occurs when a language model generates output that sounds authoritative but is factually wrong — invented legal citations, non-existent article numbers, fabricated statistics, or wrong tax rates stated with absolute confidence. The model isn’t lying. It’s predicting the most probable next word based on patterns in its training data. When those patterns don’t contain the specific Belgian legal provision you need, it fills the gap with something that sounds right.

LLMs don’t retrieve information. They generate plausible text. The difference is the gap between a librarian who checks the shelf and a colleague who answers from memory — and never admits when they’re guessing.

Why tax law is hallucination territory

Not all domains are equally vulnerable. Ask an LLM to summarize a news article, and hallucinations are an inconvenience. Ask it about Art. 344 WIB — the Belgian general anti-abuse provision — and you’re in a minefield.

Three factors make tax law uniquely dangerous:

Precision dependency. The difference between 0.12% and 1.32% TOB (taks op beursverrichtingen, Belgium’s stock exchange tax) is the difference between correct advice and a liability claim. LLMs optimize for plausible text, not precise numbers. “Close enough” doesn’t exist in professional tax work.

Reference density. A single Belgian tax answer might need Art. 19bis WIB, the Vlaamse Codex Fiscaliteit, a DVB advance ruling, and a Fisconetplus circular — simultaneously. General-purpose AI has never processed most of these documents. So it generates references that look like real ones.

Temporal instability. Belgian tax law changes constantly. The corporate tax rate, TOB thresholds, regional inheritance tax brackets — all moving targets. An LLM trained six months ago gives you yesterday’s law with today’s confidence.

The five tells: how to spot a hallucinated tax answer

Hallucinations leave fingerprints. After analyzing hundreds of AI-generated tax responses, five patterns emerge consistently:

| Tell | What it looks like | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Confidence without source | Definitive answer, no article citation | ”The TOB rate is 0.35%” — which instrument? Under what conditions? |

| The too-perfect reference | Plausible-sounding article that doesn’t exist | An article number with subsections that pattern-matches real Belgian tax law but can’t be found in WIB 92 |

| Jurisdiction bleed | Rules from the wrong country presented as Belgian | Dutch withholding tax rules applied to a Belgian taxpayer |

| Temporal blindness | Current rates for a historical question | 2026 corporate tax rate given for a 2019 assessment year |

| Missing qualifications | Clean answer where the law is messy | One TOB rate given when three apply depending on fund classification |

The last tell is the most dangerous. A fabricated article number is easy to catch — you look it up and it doesn’t exist. An incomplete answer that sounds complete? That’s where professionals get burned and clients lose money.

A model that never says “I don’t know” is lying more often than you think.

The confidence-competence inversion

Here’s the counterintuitive truth about AI progress: as models get better at language, they get worse at signaling when they don’t know.

GPT-3 hallucinated obviously — clumsy text, visible errors. GPT-4 hallucinates eloquently. The fabricated legal reference comes wrapped in fluent legal terminology, complete with conditions and exceptions that pattern-match real tax law.

OpenAI researchers documented this dynamic in 2025: training objectives reward confident prediction over honest uncertainty. The model that says “I’m not sure” gets penalized in benchmarks. The model that invents a plausible answer gets rewarded.

This isn’t a bug to be patched. Xu et al. proved formally in 2024 that hallucination is mathematically inevitable for LLMs used as general problem solvers. Not difficult to eliminate. Not a temporary limitation. Impossible — by proof.

We call this the confidence-competence inversion: the better the language, the harder it becomes to distinguish knowledge from fabrication. Each model generation makes hallucinations more dangerous, not less.

But RAG fixes this — right?

Partially. Retrieval-Augmented Generation — where the AI searches real documents before answering — reduces hallucinations significantly. The Stanford team found RAG-based legal tools hallucinate at 17–33%, compared to 58–88% for general models. That’s real progress.

But 17% is not zero. One in six queries returning fabricated information is not a rounding error — it’s a professional risk. And the remaining hallucinations are the hardest kind: they cite real-looking sources, match the format of accurate answers, and give no signal that anything is wrong.

The Orde van Vlaamse Balies acknowledged this reality in their AI guidelines: lawyers must critically verify all AI output, including cited sources and case law. Professional responsibility stays with you, regardless of which tool generated the answer.

Internationally, courts are enforcing this with increasing severity. By late 2025, over 700 documented cases of AI-hallucinated content had appeared in legal proceedings worldwide. Sanctions range from $2,000 to over $31,000 per incident. In August 2025 alone, three separate US federal courts sanctioned lawyers for filing AI-fabricated citations.

The verification stack: three defenses that work

Hallucinations can’t be eliminated. But they can be caught. Three architectural defenses, layered together, reduce the risk from systemic to manageable:

| Defense | What it does | What it catches |

|---|---|---|

| Source-grounded retrieval | Searches a curated legal corpus before generating | Prevents inventing facts the model never retrieved |

| Citation validation | Checks every cited source against the actual corpus | Catches fabricated references and misattributed content |

| Confidence scoring | Signals uncertainty explicitly on every claim | Flags thin evidence before you rely on it |

No single layer is sufficient. Source-grounded retrieval still hallucinates — Stanford proved that. Citation validation catches fabricated references but not subtle misinterpretations. Confidence scoring flags uncertainty but needs calibration.

The combination is what matters. Each layer catches what the others miss.

The cost of false certainty is always higher than the cost of honest uncertainty.

Related articles

- I asked ChatGPT and Auryth the same Belgian tax questions — here’s what happened

- What is RAG — and why it matters for tax professionals

- What is confidence scoring — and why is it more honest than a confident answer?

How Auryth TX applies this

Auryth TX is built on the assumption that hallucinations are inevitable — and designs around them rather than pretending they won’t happen.

Every answer passes through a three-layer verification pipeline: retrieval from the curated Belgian legal corpus (not the open internet), post-generation citation validation that checks every referenced provision against the actual text, and per-claim confidence scoring that explicitly flags when evidence is thin.

When the system doesn’t find sufficient sources, it tells you. When sources conflict, it shows both sides. When a cited provision has been amended since the relevant assessment date, it flags the temporal discrepancy.

The goal isn’t to be right 100% of the time. It’s to always tell you how much you can trust the answer.

See how Auryth TX handles verification →

Sources: 1. Dahl, M. et al. (2024). “Large Legal Fictions: Profiling Legal Hallucinations in Large Language Models.” Journal of Legal Analysis, 16(1), 64–93. 2. Magesh, V. et al. (2025). “Hallucination-Free? Assessing the Reliability of Leading AI Legal Research Tools.” Journal of Empirical Legal Studies. 3. Xu, Z., Jain, S. & Kankanhalli, M. (2024). “Hallucination is Inevitable: An Innate Limitation of Large Language Models.” arXiv:2401.11817. 4. Kalai, A.T., Nachum, O., Vempala, S.S. & Zhang, E. (2025). “Why Language Models Hallucinate.” OpenAI.