"I don't trust AI for tax advice" — and you're right. Here's why you should try it anyway.

AI skepticism in tax is rational. Most tools deserve it. But rejecting the entire category because ChatGPT hallucinated a tax rate is like refusing calculators because the first ones jammed.

By Auryth Team

You tried ChatGPT for a Belgian tax question. It gave you a confident answer with the wrong rate, the wrong article, or a citation that doesn’t exist. You closed the tab, told your colleagues it’s useless, and went back to Fisconetplus.

That was the right call. For that tool.

But somewhere between “ChatGPT is unreliable” and “AI can’t do tax work,” a logical leap happened that’s now costing you more than you realize.

The ChatGPT hangover

There’s a pattern playing out across every tax firm in Belgium right now. A partner or senior associate tests ChatGPT on a real question — maybe the TOB rate for accumulating funds, maybe the inheritance tax brackets for Brussels. The answer comes back confident, articulate, and wrong in ways that would have caused real damage if it had reached a client.

The professional draws the obvious conclusion: AI can’t handle tax work. And from that single experience, an entire technology category gets dismissed.

The data confirms this is widespread. AI adoption among tax and accounting professionals quadrupled from 9% to 41% between 2024 and 2025, according to the Wolters Kluwer Future Ready Accountant Report. But that means 59% still aren’t using AI tools at all — and the primary barriers aren’t cost or access. They’re trust and prior bad experiences.

The irony is that the skeptics are the ones who understand the problem best. They know tax work requires temporal precision, jurisdictional awareness, and source verification. They know a wrong rate in a tax return isn’t a minor inconvenience — it’s a professional liability issue. Their standards are exactly right. Their conclusion just happens to be wrong.

What you actually rejected

When you dismissed “AI for tax,” you were rejecting a specific architecture: a general-purpose language model with no access to current law, no concept of Belgian jurisdictions, and no way to verify its own output.

That’s not what purpose-built legal AI does.

The distinction matters the same way it mattered in 2004 when John D. Lee and Katrina See published their foundational research on trust in automation. They identified three factors that determine whether professionals trust a tool: performance (does it work reliably?), process (can I understand how it works?), and purpose (was it built for my use case?).

ChatGPT fails all three for tax work. It hallucinates sources, its reasoning is opaque, and it was built to chat — not to navigate Art. 344 §1 WIB 92 through three layers of exceptions.

But the Lee and See framework also describes what happens after a malfunction: trust drops, and it recovers — if the system demonstrates reliable performance over subsequent interactions. The problem with the ChatGPT hangover is that there are no subsequent interactions. Professionals tried one tool, drew a category-level conclusion, and stopped experimenting.

The calculator precedent

This isn’t the first time a profession rejected a tool that would eventually become indispensable.

In the 1970s, the UK Inland Revenue explicitly told staff that “under no circumstances were calculators to be used when performing tax calculations.” Accountants were expected to do the math by hand. Through the decade, new employees at CPA firms received a desk, a chair, and an adding machine — with employers contributing at most $50 toward a calculator if the employee wanted one.

By the 1980s, technology was transforming accounting, though as one historian noted, “it would be misleading to say it was embraced with enthusiasm” — the level of technological expertise among accounting firms as recently as 1989 “was in a God-awful state.”

Nobody checks the calculator’s math anymore. Not because calculators earned blind trust, but because they earned appropriate trust through consistent, verifiable performance on tasks that were clearly within their capability.

The question for AI in tax isn’t whether you should trust it blindly. Of course you shouldn’t. The question is whether you’ve tested whether the right tool, applied to the right tasks, produces verifiable results that save you time.

The trust spectrum you’re ignoring

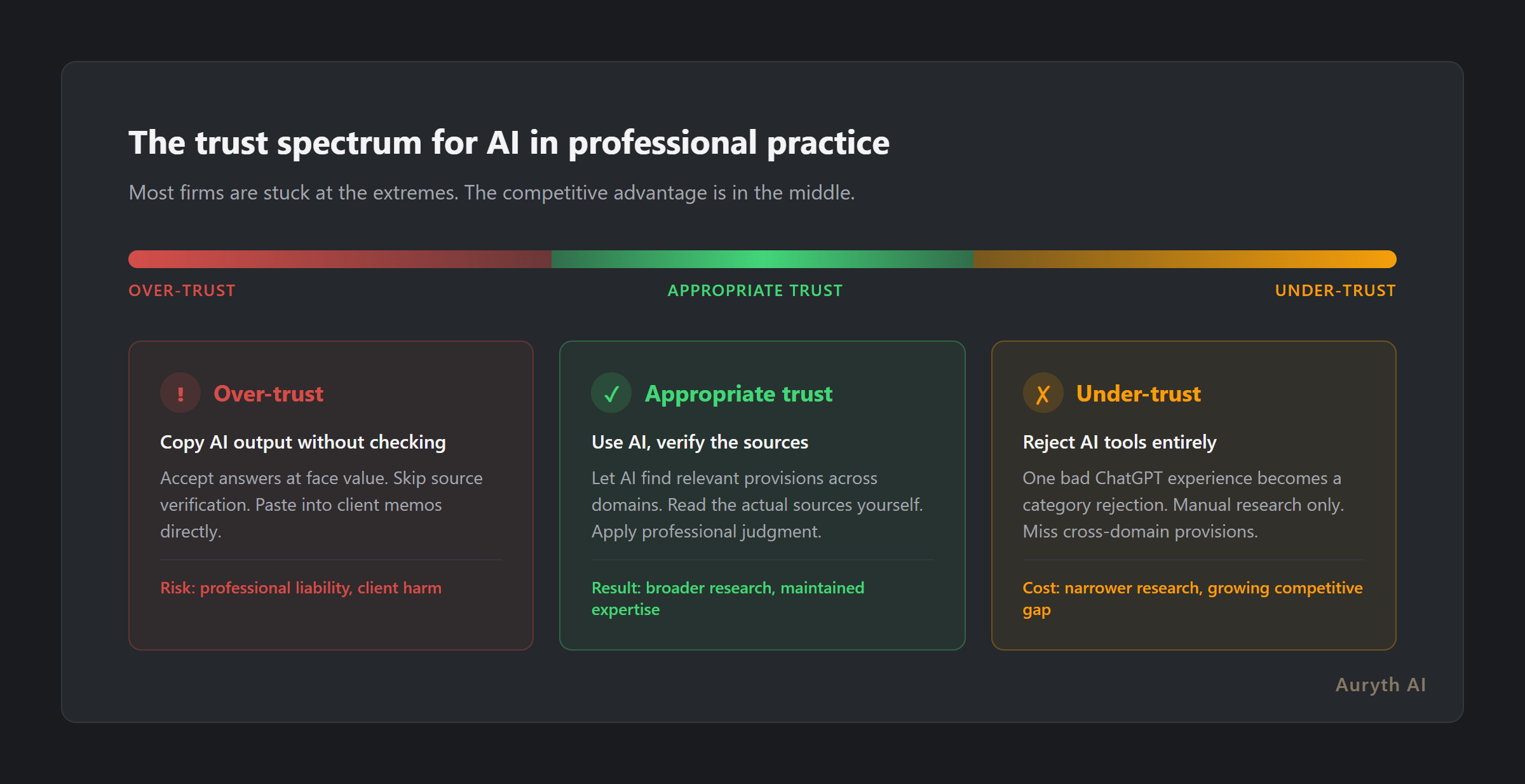

Lee and See’s research describes three positions on a trust spectrum:

- Over-trust: accepting AI output without verification. This is what happens when someone copies ChatGPT’s answer into a client memo without checking the sources. Dangerous — and exactly what skeptics fear.

- Under-trust: rejecting AI tools entirely based on a single bad experience. This is the ChatGPT hangover. Safe in the short term, costly in the long term.

- Appropriate trust: using AI for what it’s built to do, verifying at the boundaries, and maintaining professional judgment on the conclusions.

Most of the conversation about AI in professional services is stuck arguing between the first two positions. The firms that will outperform are the ones that find the third.

What appropriate trust looks like in practice

Appropriate trust isn’t about believing the AI. It’s about verifying the sources it shows you.

When a purpose-built tax research tool returns an answer, it shows you which legal provisions it retrieved, which version of the law it applied, and which jurisdiction it pulled from. You don’t have to trust the AI’s interpretation — you read the actual sources, the same way you’d read the results of a Fisconetplus search.

The difference is scope and speed. A manual Fisconetplus search on an ETF conversion might surface the TOB implications and miss the Art. 19bis angle, the withholding tax treatment, and the reporting obligations. Not because you’re careless, but because cross-domain retrieval requires knowing which domains to search — and nobody searches five databases when they think they’ve found the answer in the first one.

Purpose-built tools with domain taxonomy do that traversal systematically. They flag which domains were covered and which weren’t. You still make the professional judgment call. You just make it with broader coverage than manual research typically achieves.

The competitive math

Here’s where skepticism stops being protective and starts being expensive.

Thomson Reuters reports that organizations with strategic AI adoption are 2x more likely to see revenue growth and 3.5x more likely to experience critical operational benefits. Among tax and accounting firms, 83% of those using AI reported increased revenue in 2025, up from 72% the previous year.

One firm using AI tax preparation tools reported 90% fewer compliance errors year-over-year and prepared 55% more returns per preparer with similar staffing.

These aren’t hypothetical projections. They’re measured outcomes from firms that moved past the ChatGPT hangover and found tools built for their actual work.

The competitive gap isn’t dramatic yet. It’s a few hours here, a missed provision there. But it compounds. The firms doing AI-assisted research aren’t just faster — they’re finding provisions that manual research systematically misses. Every cross-domain question where AI surfaces three additional relevant tax domains is a question where the non-AI firm delivered narrower advice without knowing it.

And 76% of accounting graduates say they’re more likely to join firms that actively use AI. The talent pipeline is already pricing in the technology gap.

The pragmatic path

You don’t have to change your mind about AI. You have to test one tool on twenty questions and check the results yourself.

Not ChatGPT. Not a general-purpose assistant. A tool built for Belgian tax, with source citations, temporal versioning, and jurisdictional tagging.

Ask it the questions you already know the answers to. Check every source it cites. Verify every article number. Count how many times it’s right, how many times it’s wrong, and how many times it surfaces a provision you hadn’t considered.

If it fails your test, you’ve lost an hour. If it passes, you’ve found a research accelerator that makes your expertise more thorough, not less relevant.

The professionals who adopt first aren’t replacing their judgment. They’re extending their reach. And the gap between firms that research across five tax domains and firms that research across two will only grow from here.

Related articles

- 5 Belgian tax questions where generic AI is guaranteed to fail

- Why transparency matters more than accuracy in legal AI

- How to evaluate a legal AI tool: 10 questions that actually matter

- AI hallucinations: why ChatGPT fabricates sources (and how to spot it)

How Auryth TX addresses the trust problem

Auryth TX was built by tax professionals who share every concern in this article. We didn’t build a chatbot and add tax data. We built a research tool and added AI.

Every answer shows the legal provisions it retrieved, the version of the law it applied, and the jurisdiction it pulled from. Confidence scoring tells you how much of the relevant corpus was covered — not just whether the model feels confident. When the system isn’t sure, it says so.

You don’t have to trust the AI. You verify the sources it shows you — the same way you verify any research tool. The difference is that this one searches five tax domains when you’d normally search two.

The skeptics were right to be skeptical. We built for them.

Test it on your hardest questions — join the waitlist →

Sources: 1. Wolters Kluwer, Future Ready Accountant Report (2025). AI adoption among tax professionals 9% → 41%. 2. Lee, J.D. & See, K.A. (2004). “Trust in Automation: Designing for Appropriate Reliance.” Human Factors, 46(1), 50-80. 3. Thomson Reuters, Future of Professionals Report (2025). Strategic AI adoption and revenue correlation. 4. Bridgewater State University, “How Technology Has Changed the Field of Accounting” — 1970s calculator resistance data. 5. ITAA — Belgian Institute for Tax Advisors and Accountants. 16,000+ members, mandatory professional liability insurance.