What is confidence scoring — and why it's more honest than a confident answer

LLMs overestimate their own correctness by 20-60%. Confidence scoring doesn't fix that problem — it makes it visible. For tax professionals, that visibility is the difference between a research tool and a guessing machine.

By Auryth Team

Ask ChatGPT a Belgian tax question and you’ll get a clear, well-structured, authoritative-sounding answer. Ask it a question it can’t possibly know the answer to, and you’ll get the exact same tone. Same structure. Same confidence. No signal whatsoever that the second answer is fabricated.

This isn’t a bug. It’s how language models work. They’re trained to produce fluent, confident text — not to tell you when they’re guessing. Research across five major LLMs shows they overestimate the probability that their answers are correct by 20 to 60 percent. The harder the question, the worse the calibration gets.

For a tax professional, this uniform confidence is the most dangerous property of AI tools. It means the system treats a well-supported answer — backed by three Hof van Cassatie rulings and a clear statutory provision — identically to an answer it invented from patterns in its training data. You get no signal. You can’t tell the difference without checking every answer yourself.

Confidence scoring is the architectural response to this problem. Not a fix — a signal.

What confidence scoring actually measures

A confidence score is a numeric indicator that tells you how well-supported an answer is — not by the model’s internal certainty (which is unreliable), but by the evidence the system found.

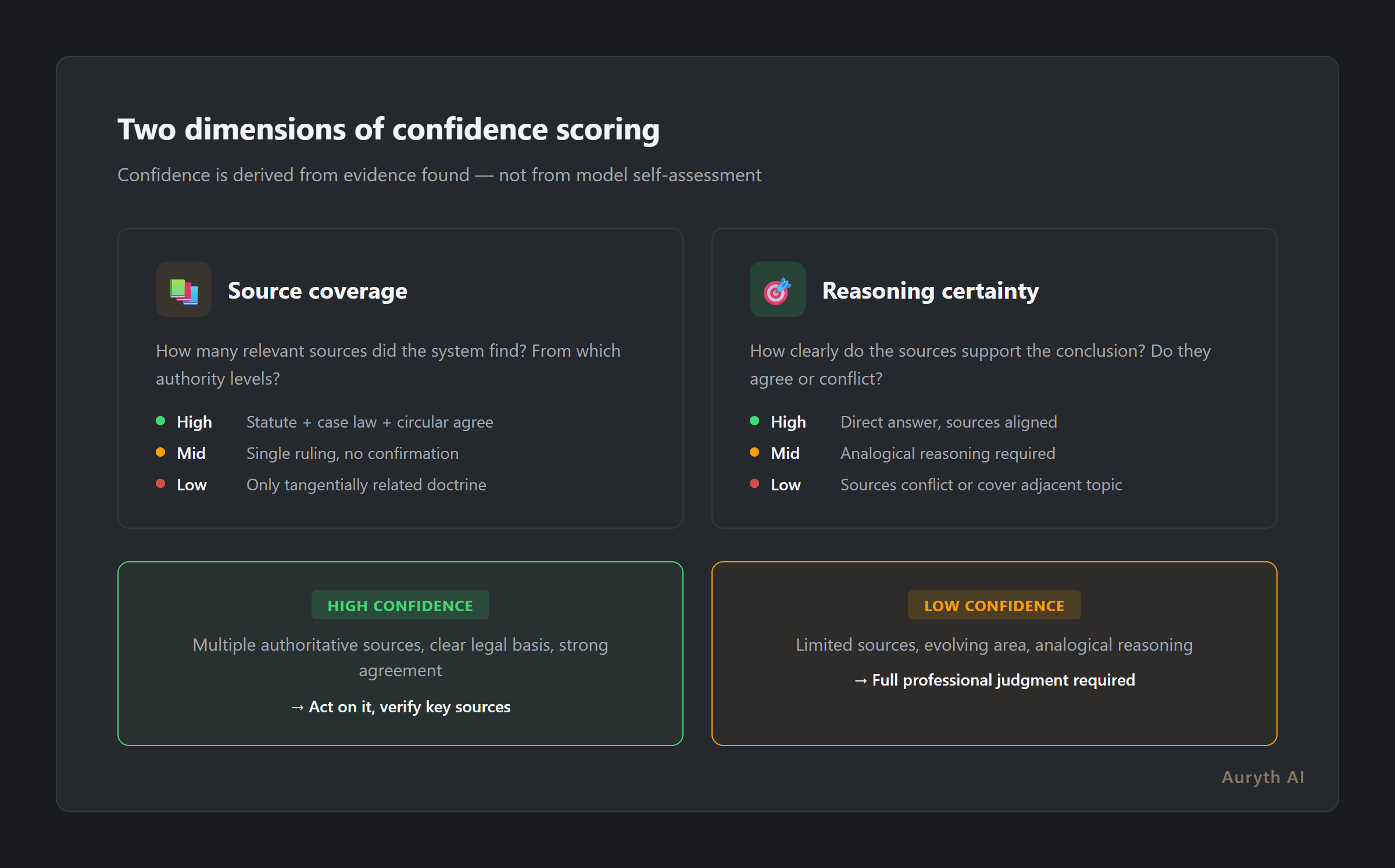

In a well-designed system, confidence has two dimensions:

Source coverage — how many relevant sources did the system find? Did it retrieve statutory provisions, case law, and administrative circulars? Or did it find a single tangentially related document?

Reasoning certainty — how clearly do the retrieved sources support the conclusion? Do they agree? Conflict? Address the exact question, or only a related one?

A high-confidence answer looks like: “Based on Art. 21 WIB 92, confirmed by Hof van Cassatie ruling of 12 March 2024 and consistent with Fisconetplus circular 2025/C/71, the dividend withholding tax rate is 30%.” Multiple authoritative sources. Clear legal basis. Strong agreement.

A low-confidence answer looks like: “Based on one DVB advance ruling from 2022, this structure may qualify for the participation exemption, though no case law was found addressing this specific configuration.” Single source. No confirmation. Analogical reasoning.

Both answers might be correct. But they demand very different levels of professional scrutiny. Without a confidence signal, they look identical.

Why LLMs are systematically overconfident

The overconfidence problem isn’t a limitation that will be fixed in the next model version. It’s structural.

Language models are trained through reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF), where human evaluators rate the quality of responses. Confident, well-structured answers consistently receive higher ratings than hedged, uncertain ones — even when both are equally accurate. The training process literally teaches models that confidence is rewarded.

Research shows that reward models used in RLHF exhibit inherent biases toward high-confidence scores regardless of actual response quality. The model learns: sounding certain gets better scores. So it sounds certain — whether or not it should.

The calibration numbers confirm this. Expected Calibration Errors across tested LLMs range from 0.108 to 0.427 — meaning the gap between stated confidence and actual accuracy is substantial. Bigger models calibrate slightly better, but even the best models remain significantly overconfident on tasks requiring domain expertise.

When an AI system says “I’m sure,” that statement tells you nothing about accuracy. It tells you about training incentives.

What uniform confidence costs in practice

Consider a Belgian tax professional asking two questions:

Question A: “What is the standard corporate tax rate for SMEs in Belgium?”

Question B: “Can a Belgian resident who transfers cryptocurrency to a foreign exchange and subsequently converts to stablecoins claim the ‘normal management of private assets’ exemption under Art. 90 WIB 92?”

A general-purpose LLM answers both with the same authoritative tone. Same formatting. Same certainty. But Question A has a straightforward, well-documented answer (20% on the first €100,000 for qualifying SMEs under Art. 215 WIB 92). Question B sits at the intersection of rapidly evolving tax policy, limited case law, and administrative positions that vary by assessment period.

Without confidence scoring, the professional must perform the same level of verification on both answers. With confidence scoring, the system flags Question A as high-confidence (multiple clear authorities) and Question B as low-confidence (limited authorities, evolving policy area, analogical reasoning required). The professional can allocate scrutiny where it matters.

That allocation isn’t laziness — it’s the definition of efficient professional practice.

The difference between model confidence and evidence confidence

Here’s a distinction most AI explainers miss: there are two entirely different kinds of “confidence” in AI systems, and only one of them is useful.

Model confidence is the probability the language model assigns to its own output tokens. This is what’s internally available in any LLM. Research shows it’s poorly calibrated and systematically overconfident. It tells you how “expected” the model’s word choices are — not whether the answer is correct.

Evidence confidence is derived from the retrieval pipeline — how many sources were found, how authoritative they are, how directly they address the question, and whether they agree. This is external to the model. It’s based on verifiable facts about what the system found, not on the model’s self-assessment.

A useful confidence scoring system uses evidence confidence, not model confidence. The score should tell you: “We found three statutory provisions, two rulings, and a circular that directly address your question, and they agree” — not “the model is 87% sure about its word choices.”

What confidence scoring can’t do

Intellectual honesty requires acknowledging the limits:

It can’t catch unknown unknowns. If the relevant provision isn’t in the corpus, the system may return a plausible answer from adjacent sources — with moderate confidence. The confidence score reflects what was found, not what exists.

Some uncertainty resists quantification. A recent paper in the Royal Statistical Society’s journal makes this point directly: “Many consequential forms of uncertainty in professional contexts resist quantification.” Whether a tax structure qualifies as “normal management of private assets” isn’t a confidence score problem — it’s a professional judgment problem. The system can show you the sources. The interpretation is yours.

Confidence scores can create false precision. A score of 0.73 vs 0.71 is meaningless noise. What matters is the categorical signal: high confidence (strong evidence, act on it), moderate confidence (some evidence, verify the key sources), low confidence (thin evidence, this needs your full professional judgment).

The right design avoids false precision by communicating in bands, not decimal points.

Related articles

- Why transparency matters more than accuracy in legal AI

- AI hallucinations: why ChatGPT fabricates sources (and how to spot it)

- How to evaluate a legal AI tool: 10 questions that actually matter

How Auryth TX applies this

Every answer in Auryth TX carries a confidence score — not derived from model self-assessment, but from the retrieval pipeline.

The score reflects three evidence dimensions: source count and authority (how many relevant sources, and what’s their legal weight), directness (do the sources address your exact question or only a related one), and consensus (do the sources agree, or is there a conflict that requires professional interpretation).

When confidence is high, you see the answer with its supporting sources and can proceed efficiently. When confidence is low, the system tells you explicitly — and shows you what it did find, what it looked for and didn’t find (negative retrieval), and where the gaps in authority lie.

We don’t pretend every answer is equally reliable. We give you the signal you need to allocate your professional judgment where it matters most.

See confidence scoring in action on a real Belgian tax question — join the waitlist →

Sources: 1. Cash, T.N. et al. (2025). “Quantifying uncert-AI-nty: Testing the accuracy of LLMs’ confidence judgments.” Memory & Cognition. 2. Leng, J. et al. (2025). “Taming Overconfidence in LLMs: Reward Calibration in RLHF.” ICLR 2025. 3. Steyvers, M. et al. (2025). “What Large Language Models Know and What People Think They Know.” Nature Machine Intelligence. 4. Delacroix, S. et al. (2025). “Beyond Quantification: Navigating Uncertainty in Professional AI Systems.” RSS: Data Science and Artificial Intelligence.