Fine-tuning vs. RAG: two ways to make AI smart — and why it matters which one your tax tool chose

Fine-tuning memorizes yesterday's law. RAG looks up today's. For Belgian tax professionals, this architecture choice determines whether your AI tool is current or confidently outdated.

By Auryth Team

Harvey, the most funded legal AI company in the world, raised over a billion dollars and built its system on fine-tuning — training a model on legal data until the knowledge is baked into its weights. If you’re evaluating AI tools for tax research, you’ll encounter this approach. You’ll also encounter RAG, retrieval-augmented generation, where the model looks up information in a curated knowledge base instead of reciting it from memory.

These aren’t just technical details. They’re architecture decisions that determine whether your AI tool can show its sources, stay current when the law changes, and tell you when it doesn’t know something. For a Belgian tax professional, that distinction matters more than any accuracy benchmark.

What fine-tuning actually does

Fine-tuning takes a pre-trained language model and retrains it on domain-specific data — court rulings, tax codes, legal commentary — until the model “absorbs” that knowledge into its parameters. Think of it as memorizing a very large, very expensive textbook.

The result: the model speaks the language of law more fluently. It recognizes legal terminology, understands reasoning patterns, and produces outputs that lawyers prefer. Harvey’s partnership with OpenAI produced a custom case law model where 97% of the time lawyers preferred its output over the base model.

But the knowledge is frozen at the point of training. Updating it means retraining — a process that costs tens of thousands per iteration and takes weeks to months. When the Belgian programmawet of July 2025 changed the investment deduction regime, a fine-tuned model trained in March 2025 wouldn’t know.

What RAG actually does

Retrieval-Augmented Generation doesn’t change the model. Instead, it gives the model access to a searchable knowledge base. When you ask a question, the system first searches the corpus, retrieves relevant documents, and then sends those documents — along with your question — to the model for answer generation.

Think of it as the difference between a colleague who answers from memory and one who walks to the library first. We covered the technical details — hybrid search, authority ranking, cross-encoder reranking — in our article on search-RAG fusion.

The critical advantage: when the law changes, you update the corpus. The model doesn’t need retraining. And because every answer is generated from retrieved documents, every claim can be traced back to a specific source.

The comparison that matters

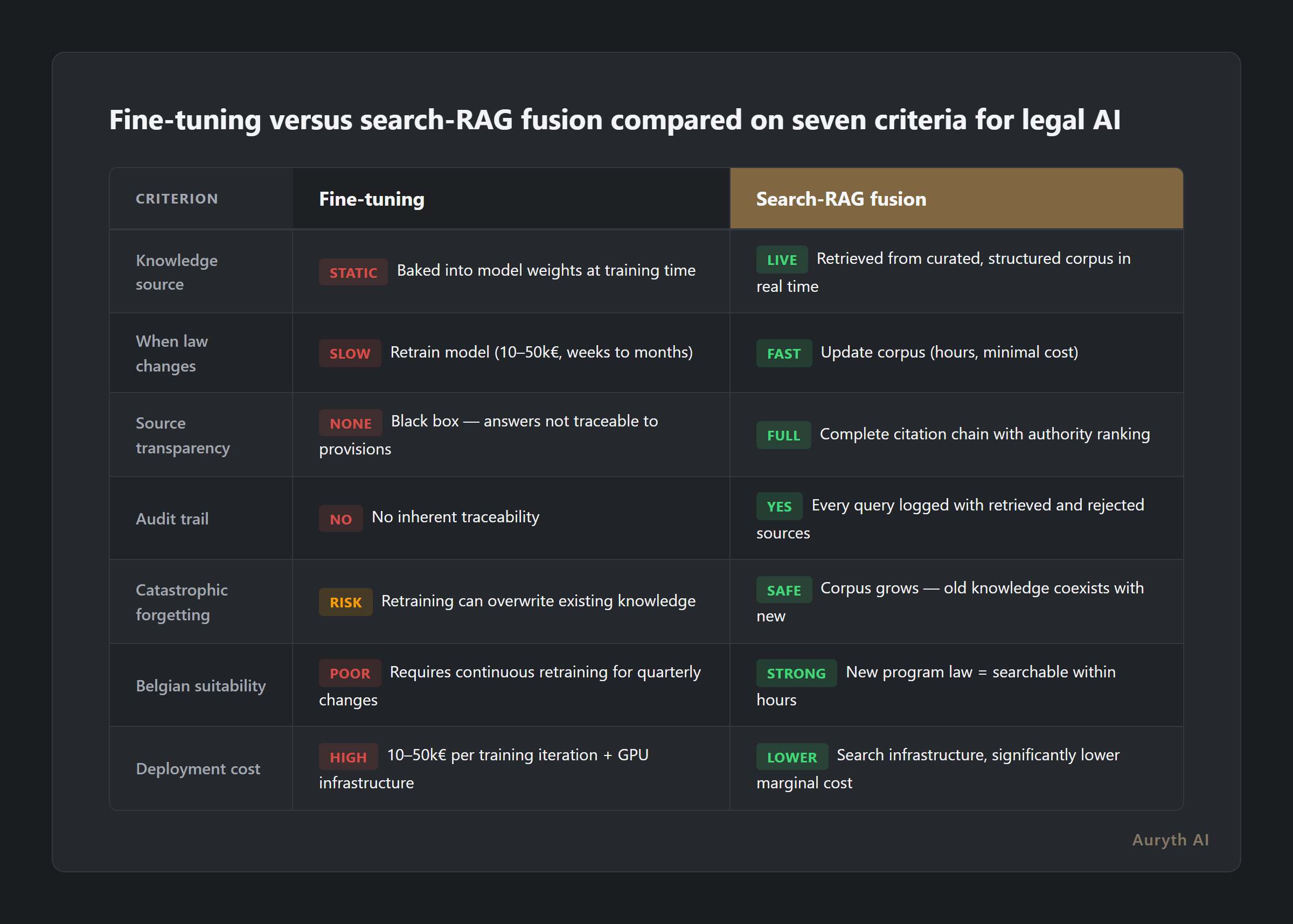

The internet is full of fine-tuning vs. RAG comparisons. Most focus on accuracy and cost. Those matter, but for legal professionals they’re not the deciding factors. Here’s what actually determines which architecture serves professional tax work:

| Criterion | Fine-tuning | Search-RAG fusion |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge source | Baked into model weights during training | Retrieved from curated, structured corpus in real time |

| When law changes | Retrain the model ($10–50k, weeks to months) | Update the corpus (hours, minimal cost) |

| Source transparency | Black box — can’t trace answers to specific provisions | Full citation chain with authority ranking |

| Audit trail | No inherent traceability | Every query logged with sources retrieved and rejected |

| Catastrophic forgetting | Retraining on new data can overwrite existing knowledge | Corpus grows — old knowledge coexists with new |

| Belgian suitability | Requires continuous retraining for a legal system that changes quarterly | New programmawet = searchable within hours |

| Cost to deploy | $10–50k per training iteration + GPU infrastructure | Search infrastructure, significantly lower marginal cost |

The transparency row is the one that should stop you. A fine-tuned model that gives you the right answer but can’t show you why — which specific article, which ruling, which circular — puts you in the same position as a colleague who says “trust me, I remember.” Professional liability requires more than memory.

Why Harvey chose fine-tuning (and why that doesn’t apply here)

Harvey’s choice makes sense for their market. US and UK law — particularly case law and contract drafting — is relatively stable. Retraining cycles of months are acceptable when the law doesn’t change quarterly. Their client base (BigLaw firms billing $500+/hour) can absorb the enterprise pricing. And their use case (contract review, document drafting, legal memo generation) benefits from the fluency advantages of fine-tuning.

Belgian tax law is a different animal. Two major program laws per year. Three regions with diverging rules. Two official languages with different legal terminologies. A reform cycle that brought a new capital gains tax, overhauled the expat regime, restructured the investment deduction, and rewrote assessment periods — all in 2025 alone.

A model trained in January 2025 is already outdated by July 2025. That’s not a theoretical concern. It’s the reality of Belgian fiscal practice.

The freshness test: if your law changes faster than your model retrains, fine-tuning is the wrong architecture.

The hybrid argument (and its limits)

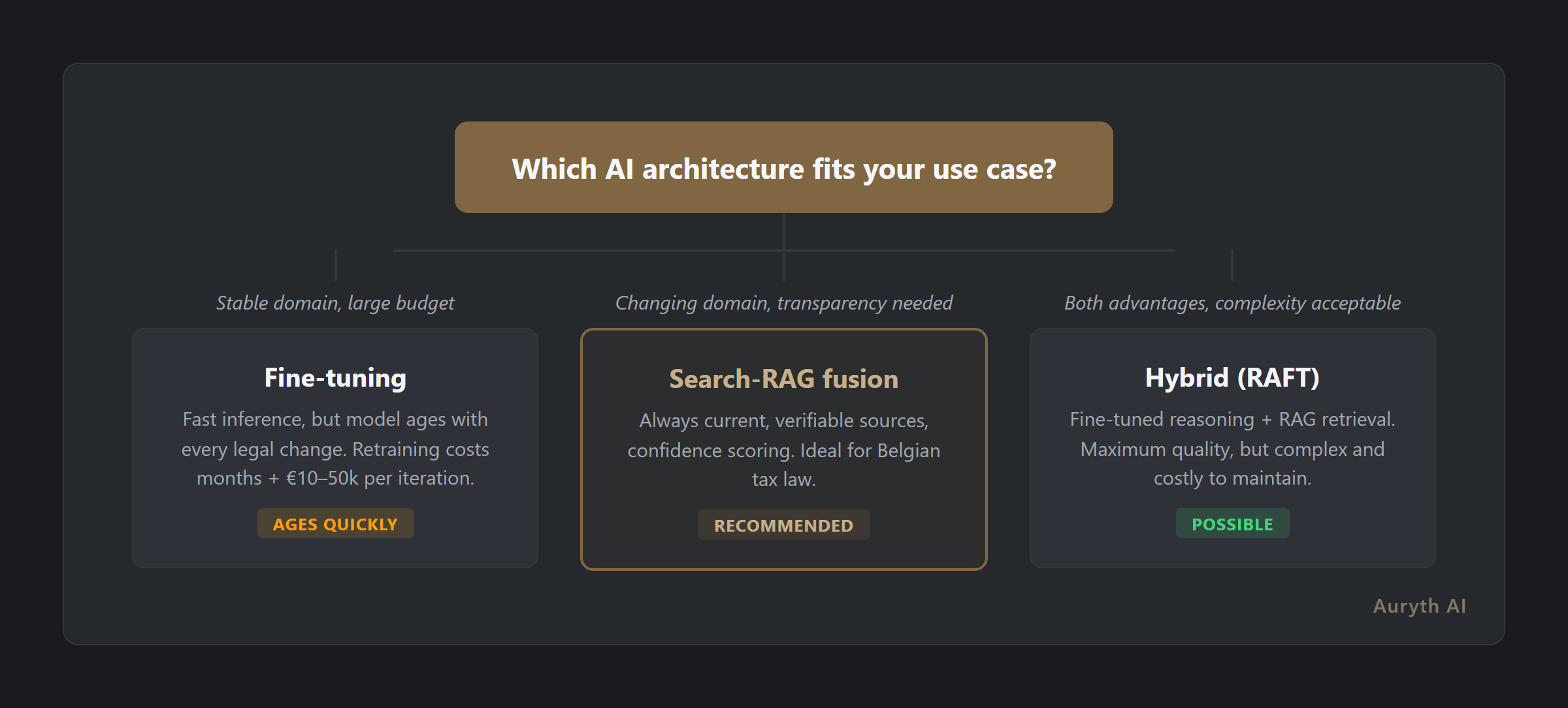

The honest answer is that the industry is moving toward hybrid approaches — fine-tuning for reasoning patterns, RAG for current knowledge. Research calls this RAFT (Retrieval-Augmented Fine-Tuning). The idea is sound: teach the model to reason like a lawyer through fine-tuning, then give it current facts through RAG.

But hybrid approaches inherit the complexity of both systems. You need expertise in model training and retrieval infrastructure. You need to keep the fine-tuned model’s knowledge synchronized with the retrieval corpus — if the model was trained on old rules but the corpus contains new ones, the result can be incoherent. And the cost equation doubles.

For Belgian tax AI, the pragmatic choice is clear: start with excellent retrieval. If fine-tuning adds value for specific reasoning tasks, add it selectively. But retrieval quality is the foundation — without it, even the best fine-tuned model can’t cite the specific article that answers your question.

Where RAG falls short

Intellectual honesty requires acknowledging RAG’s real limitations:

Retrieval quality is the ceiling. If the corpus doesn’t contain the right document, or the search pipeline doesn’t surface it, the model can’t use it. Fine-tuned models can sometimes reason by analogy in ways that pure RAG systems struggle with.

Less fluent on specialized tasks. Fine-tuned models often produce more polished, domain-native output. RAG systems generate answers from retrieved context, which can feel less “lawyerly” in tone.

Pipeline complexity. A five-stage search-RAG fusion pipeline has more moving parts than a single fine-tuned model call. More components means more potential failure points.

The tradeoff is real. But for professional tax research — where verifiability matters more than fluency, and currentness matters more than polish — the tradeoff favors retrieval.

Related articles

- What is RAG — and why it’s not enough for legal AI on its own

- Why transparency matters more than accuracy in legal AI

- AI hallucinations: why ChatGPT fabricates sources (and how to spot it)

How Auryth TX applies this

Auryth TX chose search-RAG fusion — not because fine-tuning is bad, but because Belgian tax law demands an architecture that can keep up.

Every question runs through a five-stage pipeline: hybrid search (BM25 + vector embeddings), authority ranking across the Belgian legal hierarchy, cross-encoder reranking, structured answer generation with per-claim citations, and post-generation citation validation. The knowledge base is the Belgian legal corpus — WIB 92, VCF, Fisconetplus, DVB rulings, court decisions — all structured with temporal metadata and jurisdiction tags.

When the programmawet of July 2025 restructured the investment deduction regime, our corpus reflected the change within hours. A fine-tuned model would need retraining. Ours needed a corpus update.

We don’t ask you to trust the model’s memory. We ask you to check the sources it retrieves. That’s the architecture decision that makes this possible.

See how our pipeline handles real Belgian tax questions — join the waitlist →

Sources: 1. Harvey AI (2025). “Harvey Raises Series E.” Blog announcement. 2. Soudani, H., Kanoulas, E. & Hasibi, F. (2024). “Fine Tuning vs. Retrieval Augmented Generation for Less Popular Knowledge.” arXiv:2403.01432. 3. Magesh, V. et al. (2025). “Hallucination-Free? Assessing the Reliability of Leading AI Legal Research Tools.” Journal of Empirical Legal Studies.