How hybrid search works — and why your legal AI tool probably uses only half the equation

Keyword search finds exact article numbers. Semantic search finds related concepts. Hybrid search does both — and the difference is measurable.

By Auryth Team

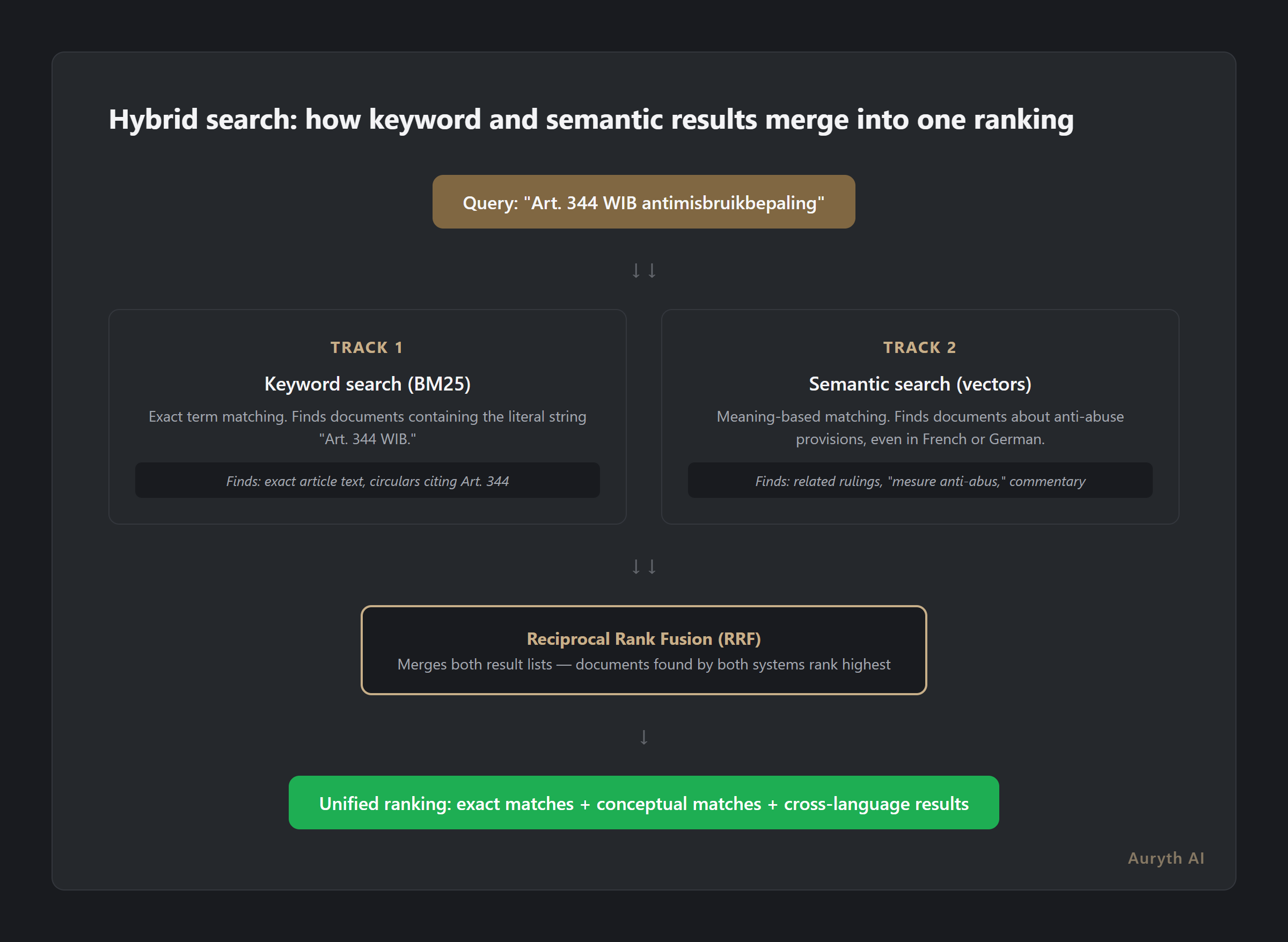

Search for “Art. 344 WIB” in a legal AI tool. You should get Belgium’s general anti-abuse provision. Now search for “antimisbruikbepaling.” You should get the same result. Most tools get one right and miss the other — because they’re using only half the search technology they need.

This isn’t a theoretical problem. At the COLIEE 2021 competition for legal case retrieval, a basic keyword search algorithm (BM25) placed second overall, beating most neural approaches. Meanwhile, the BEIR benchmark shows that pure keyword search scores 43.42 on nDCG@10, while hybrid search scores 52.59 — a 21% improvement. Neither approach alone is sufficient. Together, they outperform everything else.

Two types of search, two types of blindness

Keyword search (BM25) counts words. It is fast, precise, and excellent at finding exact article numbers, legal citations, and technical terms. When a Belgian tax professional searches for “Art. 19bis WIB,” keyword search finds every document containing that exact string. No ambiguity, no guessing.

But keyword search is blind to meaning. Search for “belasting op meerwaarden uit fondsen” (tax on capital gains from funds) and it won’t find documents that discuss the same concept using different words — “Reynders-taks” or “roerende voorheffing op beleggingsfondsen.” Same concept, different terms, zero results.

Semantic search (vector embeddings) understands meaning. It converts text into mathematical representations where similar concepts cluster together. Search for “anti-abuse provision” and it finds documents about “antimisbruikbepaling,” “mesure anti-abus,” and “Missbrauchsbestimmung” — even across languages. It understands that these terms describe the same legal concept.

But semantic search has its own blind spot. It sometimes misses exact references. Search for “Art. 344 WIB” and a pure semantic system might return documents about anti-abuse provisions generally — including the wrong article from the wrong jurisdiction. The precision that legal work demands is exactly what semantic search sometimes lacks.

| Keyword search (BM25) | Semantic search (vectors) | Hybrid search | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exact article numbers | Precise match | May miss or confuse | Precise match |

| Concept synonyms | Misses completely | Finds naturally | Finds naturally |

| Cross-language | Fails | Works well | Works well |

| Specificity | High | Variable | High |

| Conceptual breadth | None | High | High |

Keyword search tells you what a document says. Semantic search tells you what a document means. You need both.

How hybrid search combines them

Hybrid search runs both queries simultaneously: a keyword search that finds exact matches, and a semantic search that finds conceptual matches. The results are then merged using a technique called Reciprocal Rank Fusion (RRF) (Cormack et al., 2009).

The principle is elegant. A document that appears at rank 1 in keyword results and rank 3 in semantic results gets a combined score that reflects its relevance in both systems. A document that ranks highly in only one system still appears — but lower. Documents that both systems consider relevant rise to the top.

This matters because the two systems catch each other’s blind spots. Keyword search ensures that “Art. 344 WIB” is found exactly. Semantic search ensures that discussions about anti-abuse provisions under different names are also included. The fusion layer ranks documents that match on both dimensions highest.

Research from Karpukhin et al. (2020) quantified this: in open-domain question answering, hybrid retrieval achieves 53.4% top-1 passage recall, compared to 48.7% for dense (semantic) retrieval alone and just 22.1% for BM25 alone. Hybrid doesn’t just split the difference — it exceeds both.

Why this matters more in legal than in general search

Most search benchmarks use general-knowledge datasets — Wikipedia articles, web pages, forum posts. Legal documents are different in ways that make hybrid search not optional, but essential:

Exact references are load-bearing. In general search, getting “roughly the right page” is fine. In tax law, the difference between Art. 19bis WIB (Reynders tax on fund capital gains) and Art. 19 WIB (general taxable income definition) is the difference between correct advice and malpractice. Keyword precision isn’t a nice-to-have — it’s a professional requirement.

Terminology is fragmented. Belgian tax law exists in Dutch, French, and German. The same code is WIB 92 in Dutch and CIR 92 in French. The same concept may have different names across commentary, case law, and administrative circulars. Semantic search bridges this gap; keyword search alone creates silos.

Cross-referencing is structural. A single Belgian tax provision may reference royal decrees, EU directives, regional codes, and administrative positions. A search for one provision should surface related instruments — but only if they’re actually related, not just because they share common words. This requires both semantic understanding and exact matching.

The COLIEE 2021 results confirm this: in legal retrieval specifically, BM25 remains disproportionately important. But it’s not enough alone — the winning approaches combined it with semantic methods (Rosa et al., 2021).

The blind spot most AI tools don’t mention

Many legal AI tools describe their technology as “advanced AI search” or “semantic understanding” without specifying whether they use keyword matching at all. Some use pure vector search — which sounds sophisticated but means they occasionally miss exact article references that a basic keyword search would catch instantly.

The test is simple: search for a specific article number (like “Art. 171, 4° WIB”) and check whether the tool returns the exact provision. Then search for the concept (“afzonderlijke taxatie van roerende inkomsten”) and check whether it finds the same provision. If it fails either test, it’s using only half the equation.

Common questions

What is the difference between hybrid search and just running two separate searches?

The fusion step is critical. Running two searches and showing both result lists would overwhelm the user with duplicates and inconsistent ranking. Reciprocal rank fusion creates a single, coherent ranking where documents relevant to both keyword and semantic criteria appear first — without requiring manual cross-referencing.

Does hybrid search make retrieval slower?

Marginally. The keyword search (BM25) is extremely fast — typically under 10 milliseconds for millions of documents. The semantic search adds vector similarity computation, typically 20-50ms. The fusion step is negligible. Total latency stays well under one second, which is imperceptible to the user.

How does hybrid search handle Belgian multilingual law?

This is where the combination is particularly powerful. Keyword search finds “Art. 344 WIB” in Dutch texts and “Art. 344 CIR” in French texts — exact matches in each language. Semantic search connects concepts across languages, understanding that “antimisbruikbepaling” and “mesure anti-abus” describe the same provision. Together, they provide full multilingual coverage without language silos.

Related articles

- What is RAG — and why it’s the only architecture that makes legal AI defensible → /en/blog/wat-is-rag-en/

- What is authority ranking — and why your legal AI tool probably ignores it → /en/blog/authority-ranking-juridische-ai-en/

- What is chunking — and why it’s the invisible foundation of legal AI quality → /en/blog/wat-is-chunking-juridische-ai-en/

How Auryth TX applies this

Auryth TX uses hybrid search as its retrieval foundation. Every query runs through both BM25 keyword matching and dense vector retrieval simultaneously, with results merged using reciprocal rank fusion. This means searching for “Art. 344 WIB” returns the exact provision, while searching for “antimisbruikbepaling” returns the same provision plus related rulings, circulars, and commentary — regardless of language.

The system covers Dutch, French, and German legal texts natively, with cross-language semantic bridging. Article numbers are matched exactly. Concepts are matched by meaning. The result is retrieval that a tax professional can trust — because it finds what keyword search catches and what semantic search understands.

Sources: 1. Cormack, G.V. et al. (2009). “Reciprocal rank fusion outperforms condorcet and individual rank learning methods.” SIGIR ‘09. 2. Karpukhin, V. et al. (2020). “Dense Passage Retrieval for Open-Domain Question Answering.” EMNLP 2020. 3. Thakur, N. et al. (2021). “BEIR: A Heterogeneous Benchmark for Zero-shot Evaluation of Information Retrieval Models.” NeurIPS 2021. 4. Rosa, G. et al. (2021). “Yes, BM25 is a Strong Baseline for Legal Case Retrieval.” COLIEE 2021.