What is a knowledge graph — and why it changes how AI navigates Belgian tax law

A search engine finds text. A knowledge graph navigates relationships: which article amends which, which ruling interprets what, which exception overrides the rule. Belgian tax law is a web of cross-references — and a knowledge graph is the map.

By Auryth Team

Ask a Belgian tax question and you rarely get a single article as the answer. You get a chain.

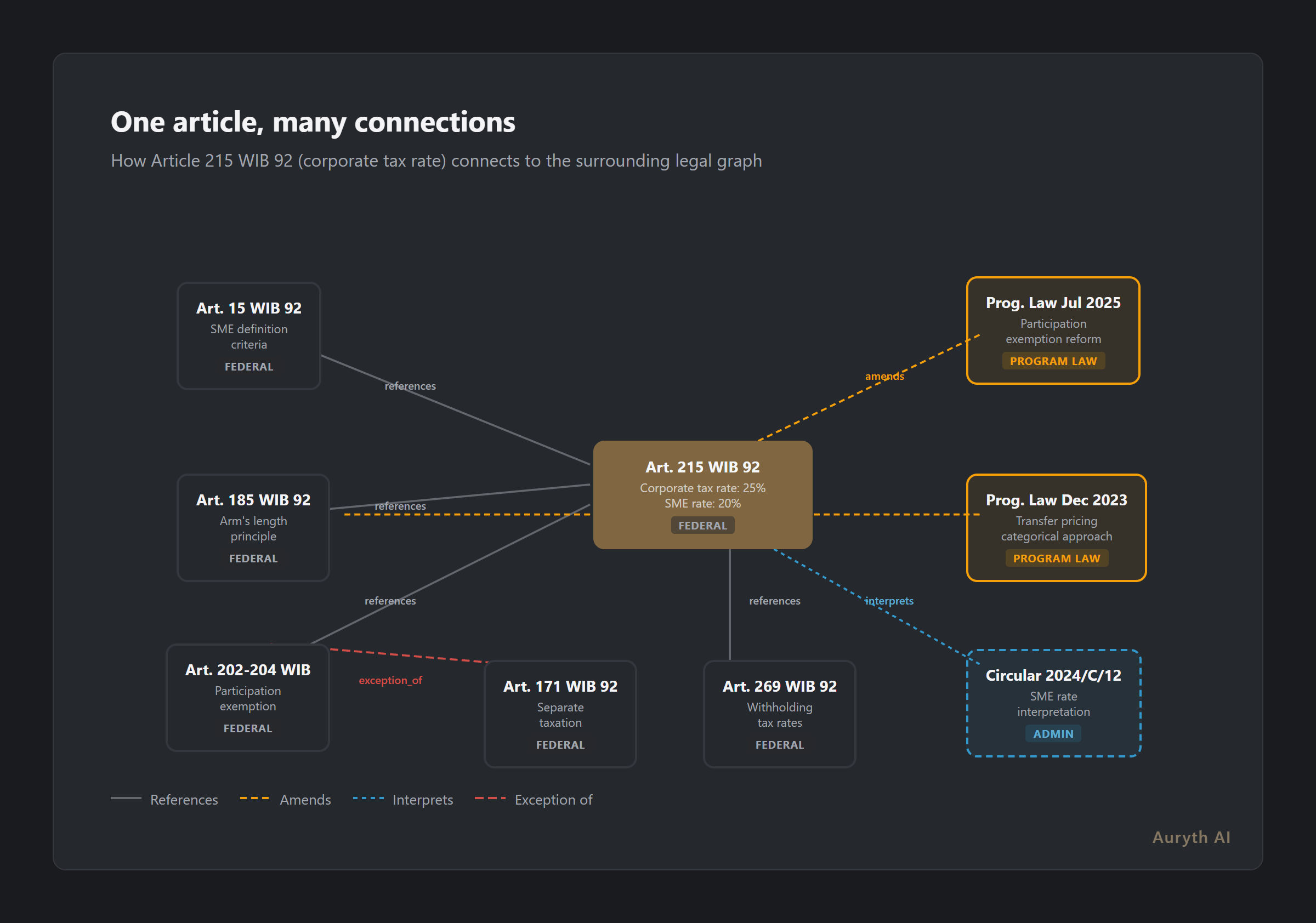

Article 215 WIB 92 sets the corporate tax rate at 25% — but references Article 185 for the arm’s length principle on transfer pricing. Article 185 was amended by the December 2023 program law, which shifted from a transactional to a categorical approach. The reduced SME rate in Article 215 itself requires meeting conditions scattered across Articles 15 and 215 §2. The withholding tax rates referenced in Article 269 were modified by the July 2025 program law. And each of these provisions has been interpreted by administrative circulars that may narrow or expand their scope.

This is not an exception. This is how Belgian tax law works. Every provision exists in a web of references, amendments, interpretations, and exceptions. A system that finds one article but misses its connections gives you a fragment, not an answer.

A knowledge graph is the data structure that captures these connections — and it fundamentally changes what a legal AI system can do.

What a knowledge graph is

A knowledge graph represents information as entities connected by typed relationships. The concept has been in computer science literature since the 1970s, but entered mainstream use in 2012 when Google launched its Knowledge Graph to move search from “matching keywords” to “understanding things.”

In a knowledge graph:

- Entities are the things: articles, laws, rulings, concepts, jurisdictions, time periods

- Relationships are the connections: “amends,” “interprets,” “cites,” “exception_of,” “applies_to”

- Properties are the attributes: effective date, jurisdiction, authority level, language version

The difference from a simple database is structural. A relational database stores records in tables with fixed schemas. A knowledge graph stores relationships directly — and can traverse them. Ask “what provisions affect the taxation of dividends from a subsidiary?” and the graph can follow the chain: Article 171 (separate taxation) → cites Article 269 (withholding rates) → references the participation exemption (Article 202-204) → which was modified by the July 2025 program law → which added a financial fixed asset requirement from tax year 2026.

No keyword search finds that chain. No vector embedding captures it. The relationships must be explicitly modeled.

Why Belgian tax law is a knowledge graph problem

Belgian tax law has characteristics that make graph-based navigation not just useful, but necessary.

Cross-references are the norm, not the exception

A single Belgian tax article routinely references 5-15 other provisions. Article 215 WIB 92 — one article about corporate tax rates — references:

- Articles 15 §1-3 (SME definition criteria)

- Article 185 §2 (arm’s length principle)

- Articles 202-204 (participation exemption)

- Article 269 (withholding tax rates)

- Article 289ter (tax credit for low-income workers)

- Multiple provisions of the program laws that amended it

Each referenced article has its own web of references. The total graph reachable from Article 215 spans dozens of provisions across multiple codes, legislative levels, and time periods.

A keyword search for “corporate tax rate Belgium” might return Article 215 itself. But the answer to a real advisory question — “does my client’s subsidiary qualify for the reduced SME rate?” — requires traversing the graph through Articles 15, 185, 202, and the relevant program law amendments.

The exception chain problem

Belgian legal drafting follows a characteristic pattern:

General rule → behoudens (except) → tenzij (unless) → mits (provided that)

These exceptions often live in different articles. The general rule for separate taxation of dividends (Article 171) has exceptions in Article 171 §2 (global inclusion option). But it also interacts with the participation exemption (Articles 202-204), which has its own conditions, exceptions, and temporal modifications.

In a flat search index, these exceptions are separate documents. In a knowledge graph, they are connected by explicit “exception_of” and “modifies” relationships — making it possible to retrieve the complete rule with all its qualifications in one traversal.

Temporal layering

Belgian tax law is amended at least twice per year through program laws — omnibus legislation that modifies dozens of provisions simultaneously. The December 2023 program law alone amended Articles 54, 185/2, 289ter/1, 321quinquies, 321sexies, 321septies, and 344 §2 of the WIB.

A knowledge graph models this through temporal version nodes: each provision has a version history, and each version records which program law created it, when it took effect, and what it replaced. The system does not merely store “Article 215 says 25%.” It stores:

- Article 215 (pre-2018): rate 33.99%

- Article 215 (2018-2019): rate 29.58%, amended by Program Law 25 December 2017

- Article 215 (2020-present): rate 25%, amended by Program Law 2 May 2019

- Article 215 (2026+): participation exemption modified, amended by Program Law 18 July 2025

Each version is a distinct node, linked to its predecessor and successor, with the amending legislation as the connecting edge.

Multi-level governance

Belgian tax provisions exist at multiple authority levels, each with different legal weight:

- EU regulations and directives — direct effect, override national law

- Federal law (WIB, BTW Code) — primary legislation

- Regional law (VCF, Code wallon, Brussels tax code) — co-equal with federal for regionalized taxes

- Royal decrees — implementing regulations

- Ministerial circulars — administrative interpretation, not binding on courts

- Advance rulings — binding on the administration for the specific case

- Case law — jurisprudence from tax courts, courts of appeal, Court of Cassation

A knowledge graph captures not just the text at each level, but the hierarchical relationships between them. When a circular interprets Article 215, the graph records that interpretation with a “interprets” edge — and flags that circulars have lower authority than the article itself. When a court ruling overrides a circular, the graph updates with an “overrules” edge.

How this differs from search

Most AI systems, including most legal AI tools, use some form of search: keyword matching, semantic similarity, or a combination. These approaches find text that looks relevant. A knowledge graph navigates structure that is relevant.

Keyword search finds documents containing the words in your query. It cannot traverse cross-references — if Article 215 mentions “Article 185” by number, a keyword search for “transfer pricing” will not follow that reference.

Vector/semantic search finds documents whose meaning is similar to your query. This is powerful for natural language questions but limited by the boundaries of individual chunks. Research on multi-hop reasoning benchmarks shows that traditional RAG often achieves below 70% accuracy when the answer requires connecting information across multiple documents.

Knowledge graph traversal follows explicit relationships. When asked “what are the conditions for the reduced SME rate?”, it starts at Article 215, follows the “references” edge to Article 15 (SME criteria), follows the “amended_by” edge to the relevant program law, and returns the complete chain — not because the text is similar, but because the legal structure connects them.

The best systems combine both: vector search for initial retrieval, knowledge graph for structured reasoning. Academic benchmarks show that graph-enhanced approaches can exceed 85% accuracy on multi-hop tasks where pure vector approaches typically plateau well below that threshold.

What the graph makes possible

A knowledge graph enables capabilities that are structurally impossible with search alone:

Impact analysis. When a new program law amends Article 215, the system can trace all provisions that reference Article 215 and flag them for review. This is not pattern matching — it is following explicit edges in the graph. The July 2025 program law’s modification to the participation exemption affects every provision that references Articles 202-204. The graph identifies them all.

Exception completeness. When retrieving a provision, the system can follow all “exception_of” edges to ensure the complete rule-plus-exceptions chain is returned. The answer to “how are dividends taxed?” is never just Article 171 §1 — it includes §2 (global inclusion option), Articles 202-204 (participation exemption), and the 2025 modifications to qualifying conditions.

Temporal precision. A query about corporate tax in 2019 follows the graph to the 2018-2019 version node (29.58%), not the current version (25%). The graph does not just store current law — it stores the complete version history and can navigate to any point in time.

Authority ranking. When multiple sources address the same question, the graph’s hierarchy enables principled ranking. An article of the WIB outweighs a ministerial circular. A Court of Cassation ruling outweighs a first-instance decision. These rankings are encoded in the graph as authority-level properties on each node.

Gap detection. If a question touches a provision that has been recently amended but the interpretation circulars have not yet been updated, the graph can flag this gap — the “interprets” edge from the old circular points to a superseded version of the article.

Why most legal AI tools do not have this

Building a knowledge graph for a legal corpus is fundamentally different from indexing documents for search. Search requires splitting text into chunks and embedding them. A knowledge graph requires:

- Structural parsing — understanding the hierarchical structure of each legal code (WIB articles, VCF’s hierarchical numbering, BTW articles and royal decrees)

- Cross-reference extraction — identifying every reference to another article, law, or ruling and creating an explicit edge

- Temporal versioning — tracking amendment history and creating version nodes for each change

- Authority classification — tagging each source with its level in the legal hierarchy

- Relationship typing — distinguishing between “amends,” “interprets,” “cites,” “exception_of,” and other relationship types

This is structured ingestion, not document dumping. It requires domain-specific parsing for every legal code and document type. The VCF’s distinctive numbering (Article 2.10.4.0.1) requires different parsing than the WIB’s traditional article-and-paragraph structure. Program laws require amendment-tracking logic that connects the amending article to every provision it modifies.

General-purpose AI tools — ChatGPT, Copilot, Gemini — do not have this structure. They process legal text as undifferentiated text. They can find passages that look relevant, but they cannot trace the chain of cross-references, amendments, and exceptions that connects one provision to dozens of others.

Even most legal AI tools use document search rather than graph navigation. Thomson Reuters and LexisNexis have invested heavily in knowledge graph technology for their platforms, but these are enterprise systems priced for large international firms. The Belgian market — smaller corpus, three regions, two official languages — has not traditionally justified this level of structural investment.

What to look for

When evaluating a legal AI tool, the presence or absence of a knowledge graph reveals itself in specific capabilities:

-

Can the tool trace cross-references? Ask a question that requires following a chain: “What conditions must my company meet for the reduced corporate tax rate?” If the answer cites Article 215 but not Article 15 (SME definition), the tool is searching, not navigating.

-

Does the tool flag amendments? If you ask about a provision that was recently modified by a program law, does the tool know about the modification? If it returns outdated text without flagging the change, the amendment chain is not modeled.

-

Can the tool distinguish authority levels? Ask a question where a ministerial circular contradicts a court ruling. If the tool presents both as equally authoritative, it has no hierarchy model — which means no graph.

-

Can the tool show you the connections? A tool built on a knowledge graph can show you which provisions connect to your answer and how. A tool built on search can only show you the text it found.

The graph is what turns a collection of legal documents into a navigable map of the law.

Related articles

- What is chunking — and why it’s the invisible foundation of legal AI quality →

- What is authority ranking — and why your legal AI tool probably ignores it →

- What is temporal versioning — and why your legal AI tool probably serves you yesterday’s law →

How Auryth TX applies this

Auryth TX does not search documents — it navigates a knowledge graph of Belgian tax law.

Every article in the WIB, BTW Code, VCF, and regional codes is a node in the graph. Every cross-reference is an edge. Every program law amendment creates a temporal version node linked to the provisions it modified. Every circular, ruling, and court decision is connected to the provisions it interprets, with its authority level explicitly modeled.

When you ask “how are dividends from a subsidiary taxed?”, the system does not just find Article 171. It traverses: Article 171 (separate taxation) → Articles 202-204 (participation exemption) → Program Law July 2025 (financial fixed asset requirement) → Article 269 (withholding rates) — and returns the complete chain with temporal context, authority ranking, and exception completeness.

The domain radar in every research result is a direct visualization of this graph: it shows which tax domains connect to your question, which provisions apply, and how they relate to each other. The connections are not inferred from text similarity. They are structural — because they were parsed, extracted, and modeled from the law itself.

Not search. Navigation. Every cross-reference traced. Every amendment linked. Every exception connected.

Sources: 1. Google (2012). “Introducing the Knowledge Graph: things, not strings.” Official Google Blog. 2. Hogan, A. et al. (2021). “Knowledge Graphs.” ACM Computing Surveys, 54(4), Article 71. 3. LexisNexis (2025). “Legal AI Software Company Evaluation Report.” GlobeNewswire. 4. de Martim, H. (2025). “An Ontology-Driven Graph RAG for Legal Norms.” arXiv:2505.00039. 5. Barron, A. et al. (2025). “Bridging Legal Knowledge and AI: RAG with Vector Stores, Knowledge Graphs.” ICAIL 2025. 6. EUR-Lex (2023). “European Legislation Identifier (ELI).” eur-lex.europa.eu.