Bilingual Belgian tax law: why NL/FR is a prerequisite, not a feature

Federal law is published in Dutch and French. Regional codes exist in one language only. Rulings follow the language of the procedure. A monolingual AI tool misses half the corpus.

By Auryth Team

A tax advisor in Antwerp researches erfbelasting for a client whose father recently passed away. They search in Dutch. They find Flemish court rulings, Vlaamse Codex Fiscaliteit provisions, and Dutch-language administrative circulars. Their research feels complete.

Except it isn’t. A French-speaking chamber of the Court of Cassation ruled on a related point six months ago — a ruling that changes the analysis. It was published in French. It exists in the Pasicrisie archives. A Dutch-only search never surfaces it.

This is not a hypothetical. It is the structural reality of legal research in Belgium: a bilingual country with a legal system that produces authoritative sources in two languages, across three regions, with partial overlap and partial separation. Any tool that searches in only one language — or treats bilingualism as a translation layer rather than a corpus architecture problem — systematically misses relevant sources.

How Belgian law is published

The bilingual structure of Belgian law is constitutionally mandated but practically complex:

| Level | Language(s) | What it means for research |

|---|---|---|

| Federal legislation | Published simultaneously in NL and FR in the Belgisch Staatsblad / Moniteur belge. Both versions have equal legal authenticity | You can cite either version. But rulings interpreting the law may exist in only one language |

| Flemish regional codes | Dutch only. The Vlaamse Codex Fiscaliteit (VCF) — which governs Flemish erfbelasting, schenkbelasting, and registratierechten — exists exclusively in Dutch | A French-language search will not find VCF provisions |

| Walloon regional codes | French only. Walloon tax codes, including droits de succession and droits de donation, exist exclusively in French | A Dutch-language search will not find Walloon provisions |

| Brussels regional codes | Bilingual (NL/FR). Both versions have equal status | Brussels is the only region where a monolingual search doesn’t miss regional sources |

| Court rulings | Issued in the language of the procedure. The Court of Cassation has Dutch-speaking and French-speaking chambers, each producing rulings in their respective language | A Dutch-only search misses French-language rulings. A French-only search misses Dutch-language rulings |

| Administrative circulars | Federal circulars are published in both NL and FR via Fisconetplus. Regional administrative guidance follows regional language rules | Coverage depends on the level of government |

| Advance rulings (DVB/SDA) | Published in the language of the application | A ruling requested in French by a Walloon taxpayer exists only in French. A Dutch-speaking advisor may never find it |

The result: no single-language search covers the full Belgian legal corpus. This is not a flaw in the system. It is a consequence of Belgium’s constitutional language structure — a structure that produces legally binding sources in two languages with partial overlap and partial separation.

Why this is harder than translation

The obvious solution — translate everything — sounds simple. It isn’t.

Legal terminology doesn’t map 1:1. Dutch and French legal terms for the same concept are not always direct translations. “Onroerende voorheffing” and “précompte immobilier” refer to the same tax, but the compound noun structures differ. “Erfbelasting” (Flemish) and “droits de succession” (federal/Walloon/Brussels) are different terms for overlapping but not identical concepts — because Flanders reformed its inheritance tax under the VCF while the other regions use a different legislative framework.

Regional law has no counterpart in the other language. The VCF is a codified, consolidated code that exists only in Dutch. There is no French version of the VCF, because it applies only to Flanders. A French-speaking researcher who needs to compare Flemish and Walloon inheritance tax provisions must read the VCF in Dutch and the Code des droits de succession in French — two entirely different documents with different structures, numbering systems, and terminology.

Court rulings carry nuance that machine translation loses. A ruling from the Dutch-speaking chamber of the Court of Cassation uses specific legal formulations that have interpretive significance. Machine-translating this ruling into French loses the nuances of Dutch legal drafting. The same applies in reverse: French judicial language has conventions that don’t survive direct translation into Dutch.

The Pasicrisie and Arresten archives were historically monolingual. Before the Tradcas project (which publishes rulings side-by-side in both languages), researchers had to consult separate databases: the Pasicrisie (French only) and the Arresten van het Hof van Cassatie (Dutch only). A researcher working in one language simply did not encounter rulings published in the other.

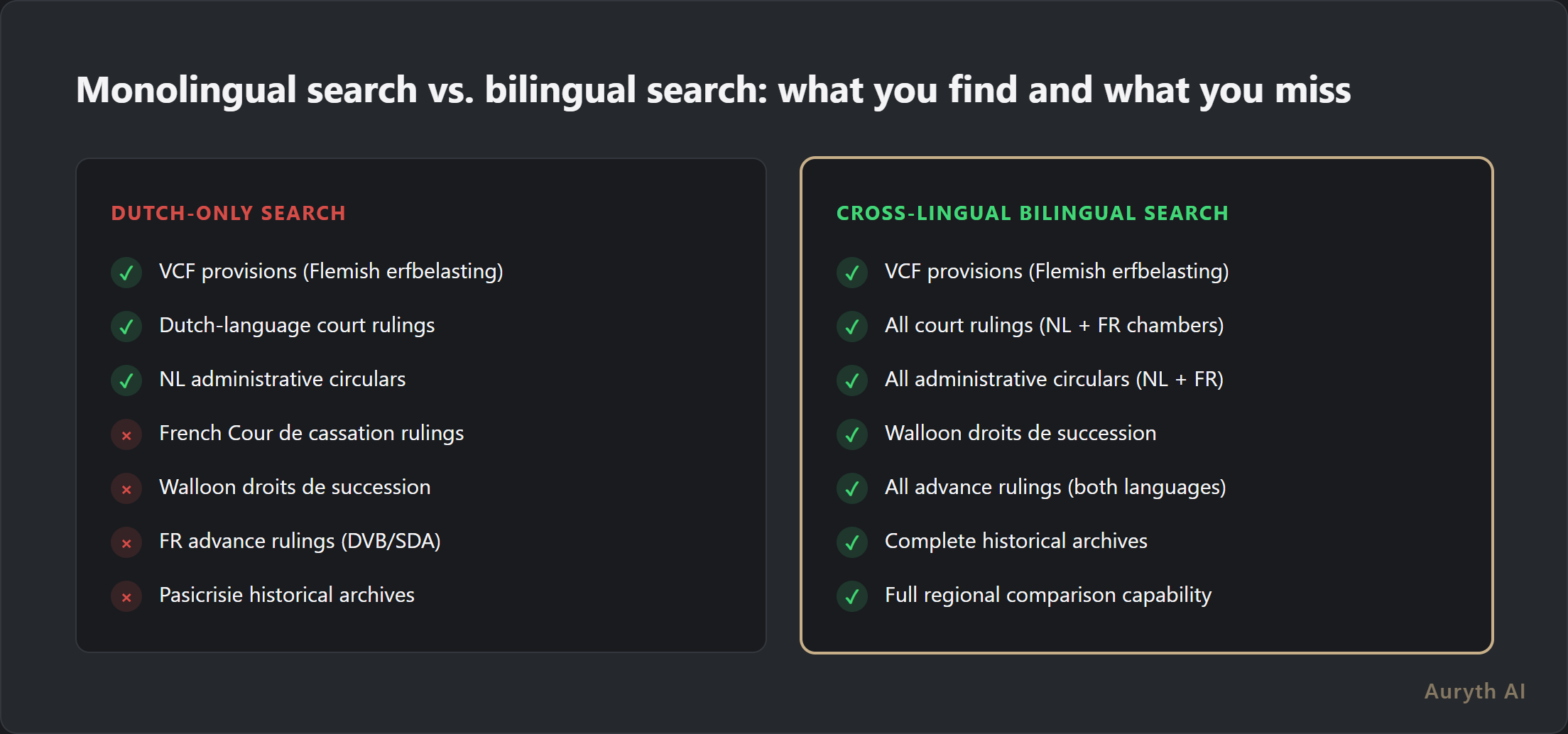

What a monolingual search misses

Consider a practical research task: a tax advisor needs to determine how life insurance products (TAK 23 / Branche 23) are treated for inheritance tax across all three regions.

A Dutch-only search would find:

- VCF provisions on Flemish erfbelasting treatment of TAK 23 products

- Dutch-language court rulings from Flemish courts

- Dutch-language administrative circulars

- Dutch-language advance rulings from Dutch-speaking applicants

A Dutch-only search would miss:

- French-language Court of Cassation rulings from the Francophone chamber

- Walloon droits de succession provisions (French only)

- Brussels regional provisions published only in French

- French-language advance rulings from Francophone applicants

- French-language doctrinal commentary

The same asymmetry applies in reverse for a French-only search — it would miss the VCF, Dutch-language rulings, and Flemish administrative guidance.

For a cross-regional comparison — which is exactly what the client needs — neither monolingual search produces a complete picture. The advisor must manually search in both languages, cross-reference the results, and synthesize a comparison. This is time-consuming, error-prone, and the kind of task where a missing source can change the entire analysis.

In a bilingual legal system, monolingual search is structurally incomplete. Not slightly incomplete. Half-the-corpus incomplete.

What cross-lingual retrieval actually requires

Solving this problem requires more than adding a translation layer. It requires architectural decisions at the corpus level:

Bilingual ingestion. Every source must be ingested in its original language with correct metadata — jurisdiction, language, temporal validity, position in the legal hierarchy. Translating everything into one language and searching that translation destroys the metadata and introduces translation errors.

Cross-language semantic matching. A Dutch query about “erfbelasting bij levensverzekeringen” must find relevant French sources about “droits de succession sur les assurances-vie” — not through keyword translation, but through semantic understanding that both queries address the same legal concept. This requires cross-lingual embedding models trained on legal text.

Terminology alignment without conflation. “Erfbelasting” under the VCF and “droits de succession” under the Brussels code are closely related but not identical — they are different laws in different languages with different rates, thresholds, and exemptions. The system must align them conceptually (both address inheritance taxation) without conflating them (they are different legal regimes).

Original-language presentation. When the system retrieves a French-language source for a Dutch-language query, it must present the source in its original French — because that is the legally authoritative text. Translation can aid comprehension, but the citation must reference the original.

Common questions

Do most Belgian tax professionals work in both languages?

It depends. In Brussels, bilingualism is common. In Flanders and Wallonia, many practitioners work primarily in one language. But even monolingual practitioners handle cases that touch both language communities — a Flemish client with Walloon real estate, a Brussels-based company with employees in all three regions. For these cases, bilingual research is not optional.

Can’t I just use Google Translate for French rulings?

For general comprehension, yes. For legal research, no. Machine translation of legal text loses the specific formulations that carry interpretive weight. A Court of Cassation ruling’s precise wording matters — the difference between “dès lors que” and “pour autant que” can change the scope of a rule. Machine translation regularizes these distinctions away.

Is Fisconetplus bilingual?

Yes — Fisconetplus publishes federal tax legislation, circulars, parliamentary questions, and case law in both Dutch and French. But it does not cover regional legislation (VCF, Walloon codes), does not have AI-powered search, and does not cross-reference Dutch and French sources or flag when the same concept is treated differently across language versions.

Related articles

- Three regions, three tax systems: why Belgian fiscal advice requires side-by-side comparison

- Why Belgium is the perfect market for specialized tax AI

- How we handle contradictory sources — and why most AI tools don’t

- What is temporal versioning — and why your legal AI tool probably serves you yesterday’s law

How Auryth TX applies this

Auryth TX ingests the complete Belgian legal corpus in both Dutch and French as a foundational architectural requirement, not as an afterthought.

Federal legislation enters the system in both language versions with explicit linking — the Dutch and French texts of the same law are connected, not stored as separate documents. Regional codes enter in their original language only (VCF in Dutch, Walloon codes in French, Brussels codes in both), with correct jurisdictional tagging. Court rulings enter in their procedural language with chamber identification.

Cross-lingual retrieval is semantic, not keyword-based. A Dutch-language query about erfbelasting finds relevant French-language sources about droits de succession through cross-lingual embeddings trained on Belgian legal text. The results are presented in their original language — because that is the legally authoritative version.

The system does not translate sources. It finds them across languages and presents them with their full linguistic and jurisdictional context. When a Flemish and Walloon provision address the same concept differently, the system shows both — in their original language, with their original legal status.

In a bilingual legal system, your research tool must be bilingual too. Not as a feature. As a foundation.

Sources: 1. European Forum of Official Gazettes (2024). “Belgium — Official Journal.” European Union. 2. Court of Cassation Belgium (2025). “Jurisprudence-Rechtspraak.” Hof van Cassatie. 3. Library of Congress (2024). “Guide to Law Online: Belgium — Legislative.” LOC Research Guides. 4. Codex Vlaanderen (2025). “Vlaamse Codex Fiscaliteit.” Flemish Government.