How we handle contradictory sources — and why most AI tools don't

When Belgian tax sources disagree, the worst thing an AI tool can do is pick one and act confident. Here's what honest uncertainty looks like.

By Auryth Team

In October 2023, the Belgian Supreme Court (Hof van Cassatie) ruled that foreign-sourced income is exempt from Belgian tax as long as it falls within the scope of the foreign tax regime — regardless of whether it was actually taxed. One year later, in October 2024, the same court ruled the opposite: income is only exempt if it was effectively taxed in the source country.

Same doctrine. Same court. Opposite conclusions.

The distinction? Treaty context — one case involved the Belgium-Netherlands treaty, the other the Belgium-Congo treaty. But for the tax professional preparing advice, the implication is the same: two authoritative sources point in different directions, and the answer depends on which one applies to your client’s situation.

Now imagine asking an AI tool this question. Most tools would give you one answer, confidently, with a citation. They would not tell you that the other ruling exists, that the doctrine is contested, or that the answer depends on treaty-specific language. That omission is more dangerous than a wrong answer — because a wrong answer might trigger verification. A confident, partial answer doesn’t.

The contradiction landscape in Belgian tax law

Contradictory sources are not bugs in the Belgian legal system. They are structural features. The system produces them reliably, for reasons that have nothing to do with error:

| Type of contradiction | Example | Why it happens |

|---|---|---|

| Chamber vs. chamber | The Dutch-speaking and French-speaking chambers of the Supreme Court reached opposite conclusions on whether the annual tax on collective investment funds qualifies as a net wealth tax (2022) | Belgium’s bilingual court system processes cases separately |

| Circular vs. ruling | The tax administration’s circular states a position; a court ruling later contradicts it — but the circular is never withdrawn | Administrative practice and judicial interpretation evolve on different timelines |

| Federal vs. regional | Federal income tax treatment of an instrument conflicts with regional gift/inheritance tax treatment of the same instrument | Three regions legislate independently within their competences |

| Temporal drift | A provision that was valid when your client structured a transaction has since been amended or reinterpreted | Programme laws change dozens of provisions twice per year |

| Doctrine vs. case law | Academic commentary argues position A; recent case law establishes position B | Scholarly analysis and judicial decisions serve different functions |

A professional who has spent fifteen years inside Belgian tax law knows these contradictions exist. They navigate them through experience, judgment, and careful reading. The question is: what happens when you add AI to this process?

The overconfidence problem

Most AI tools are optimised for confident answers. That is a design choice, not a limitation of the technology.

Large language models are structurally overconfident. Recent research on LLM calibration shows that model confidence consistently overstates correctness — what researchers call “miscalibration” (Xiong et al., 2024). When an LLM assigns 90% confidence to an answer, the actual accuracy is often substantially lower. This is not a fixable bug. It is, as the Stanford RAG hallucination study put it, “an inevitable consequence of probabilistic language modelling” (Magesh et al., 2024).

The consequences are visible. A database tracking AI hallucinations in court filings documented over 700 cases worldwide by late 2025, with 90% occurring in 2025 alone. Sanctions against lawyers range from $2,000 to $31,000 per incident — not for using AI, but for failing to verify its output (Charlotin, 2025).

The pattern is always the same: the tool presented a confident answer, the professional trusted it, and the source turned out to be fabricated or inapplicable. But there is a subtler failure mode that rarely makes headlines: the tool presented a correct answer — but hid the fact that equally authoritative sources disagree.

The most dangerous AI failure is not the wrong answer. It is the right answer that hides the existence of a contradicting one.

The three maxims — and when they fail

Legal systems have ancient tools for resolving normative conflicts:

- Lex superior — higher-ranking norms override lower ones (constitution beats statute, statute beats circular)

- Lex specialis — specific provisions override general ones

- Lex posterior — later norms override earlier ones

These maxims resolve many contradictions. When a circular contradicts a law, lex superior settles it: the law prevails. When a general rule and a specific exception conflict, lex specialis determines the outcome.

But Belgian tax practice regularly produces situations where the maxims don’t cleanly resolve the conflict:

- Two Supreme Court rulings of equal authority reaching opposite conclusions (lex posterior says the later one prevails — but was it intentionally overruling, or was the context different?)

- A circular that the administration actively enforces despite contradicting case law (lex superior says the case law prevails — but will the tax inspector follow the ruling or the circular?)

- Academic doctrine that identifies an ambiguity neither the legislature nor the courts have addressed

In these situations, there is no single correct answer. There are positions, each with different levels of support, risk, and defensibility. The professional’s job is to navigate this landscape and advise the client on which position to take and why.

An AI tool that flattens this landscape into a single confident answer is not helping. It is removing exactly the information the professional needs most.

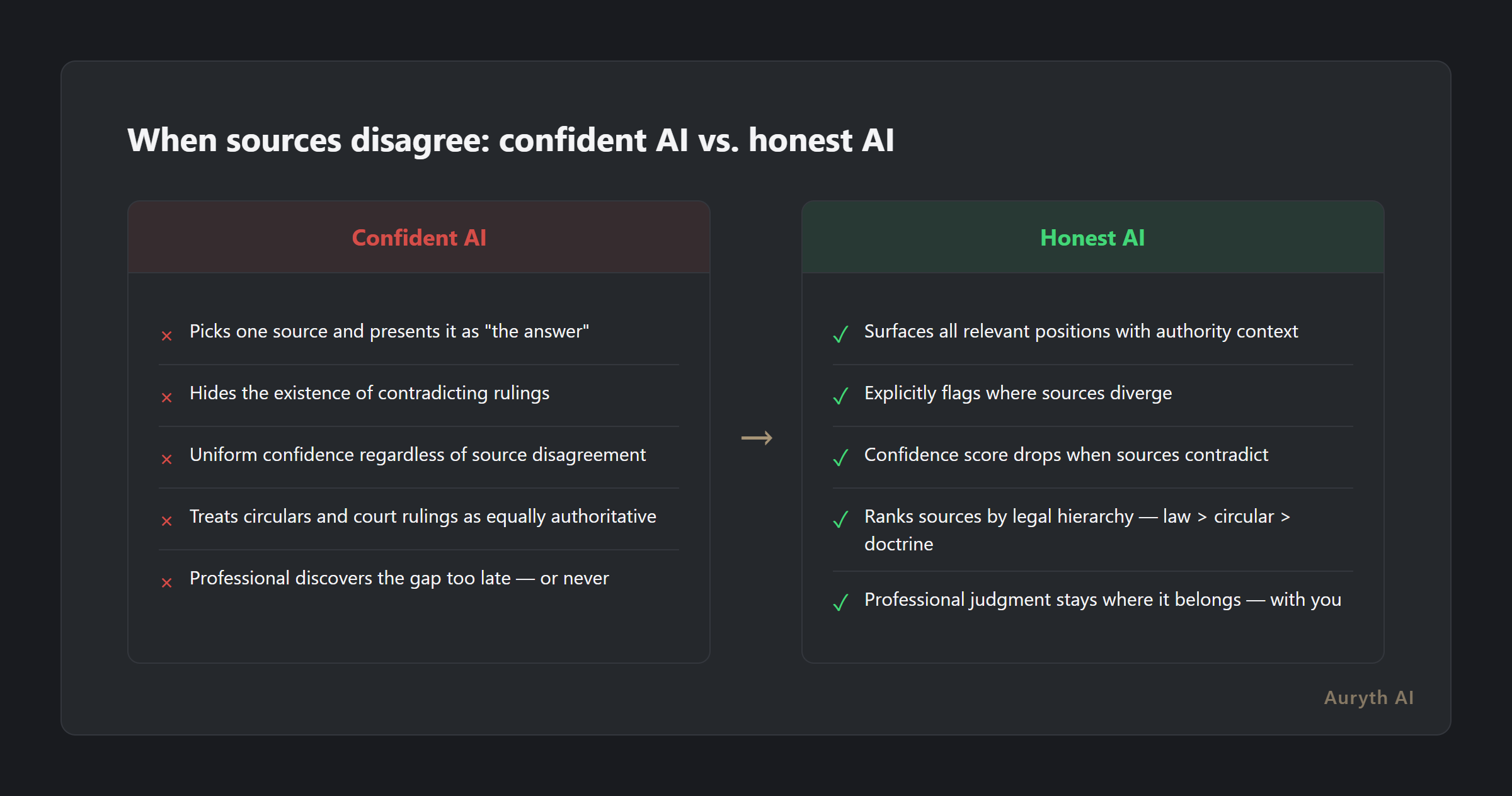

What honest uncertainty looks like

The alternative to confident answers is not vague ones. It is structured uncertainty — presenting the full picture with enough context for the professional to exercise judgment.

| What most tools do | What honest uncertainty looks like |

|---|---|

| Present one position as “the answer” | Surface all relevant positions with their authority level |

| Cite one source | Show where sources agree and where they diverge |

| Uniform confidence regardless of source quality | Confidence score that drops when sources contradict |

| No indication of ambiguity | Explicit flag: “Sources on this topic reach different conclusions” |

| Treat circulars and court rulings as equivalent | Rank by legal hierarchy — but note when the administration diverges from judicial interpretation |

This is harder to build. It requires the system to detect when retrieved sources disagree, classify the nature of the disagreement, and present the contradiction in a way that aids rather than overwhelms the professional.

But it is also what professionals actually need. A tax advisor preparing a ruling request for the DVB (Dienst Voorafgaande Beslissingen) does not want a chatbot’s opinion. They want to know: what does the law say, what does the administration say, what do the courts say, and where do these three diverge?

Common questions

Can AI really detect contradictions between legal sources?

Yes — at the retrieval level. When a system retrieves multiple sources that make opposing claims about the same legal question, natural language inference (NLI) models can identify the contradiction. The harder problem is classifying the contradiction: is it a genuine ambiguity, a resolved conflict (where lex superior settles it), or an apparent conflict caused by different factual contexts? Current systems can flag contradictions reliably. Classifying them fully still requires professional judgment.

Isn’t it better to just give the most authoritative answer?

For resolved conflicts, yes — lex superior and lex specialis should guide the response. But for genuinely contested positions, presenting only the “most authoritative” source is misleading. A Supreme Court ruling from 2023 does not automatically override a Supreme Court ruling from 2024 if they address different treaty contexts. Authority ranking is necessary but not sufficient.

How should I handle contradictory sources in my own practice?

Document everything. When sources disagree, note the contradiction explicitly in your research output. Identify which resolution maxim applies (if any). If the conflict is genuine, present the client with the competing positions and your recommendation — along with the risk profile of each position.

Related articles

- Why transparency matters more than accuracy in legal AI

- What is confidence scoring — and why it’s more honest than a confident answer

- What is authority ranking — and why your legal AI tool probably ignores it

- What the Stanford hallucination study actually revealed

How Auryth TX applies this

Auryth TX treats source contradictions as information, not errors. When the retrieval layer surfaces sources that reach different conclusions on the same legal question, the system flags the contradiction explicitly rather than silently picking one.

Each retrieved source carries its position in the Belgian legal hierarchy — constitution, legislation, royal decree, circular, case law, doctrine — so contradictions are presented with their authority context. When a circular contradicts a court ruling, the system shows both positions and identifies the hierarchy. When two court rulings disagree, the system surfaces both with their dates, chambers, and treaty contexts. The confidence score drops when sources contradict, giving the professional a clear signal that this question requires deeper analysis.

The result is not a weaker answer. It is a more complete one. The professional sees the full contradiction surface and applies their judgment — which is exactly how serious tax advice has always worked.

When sources disagree, your AI tool should tell you. Not decide for you.

Sources: 1. Magesh, V. et al. (2024). “Hallucination-Free? Assessing the Reliability of Leading AI Legal Research Tools.” Journal of Empirical Legal Studies. 2. Xiong, M. et al. (2024). “Can LLMs Express Their Uncertainty? An Empirical Evaluation of Confidence Elicitation in LLMs.” ICLR 2024. 3. PwC Legal Belgium (2025). “Confusion grows over ‘subject-to-tax’ rule for foreign-sourced income exemptions in Belgium.” PwC Belgium. 4. Charlotin, D. (2025). “AI Hallucination Cases Database.” Independent research.