What is temporal versioning — and why your legal AI tool probably serves you yesterday's law

Belgian tax law changes twice a year minimum. If your AI tool can't tell 2019 from 2026, its answer isn't wrong — it's for the wrong year. Here's what temporal versioning is and why it matters.

By Auryth Team

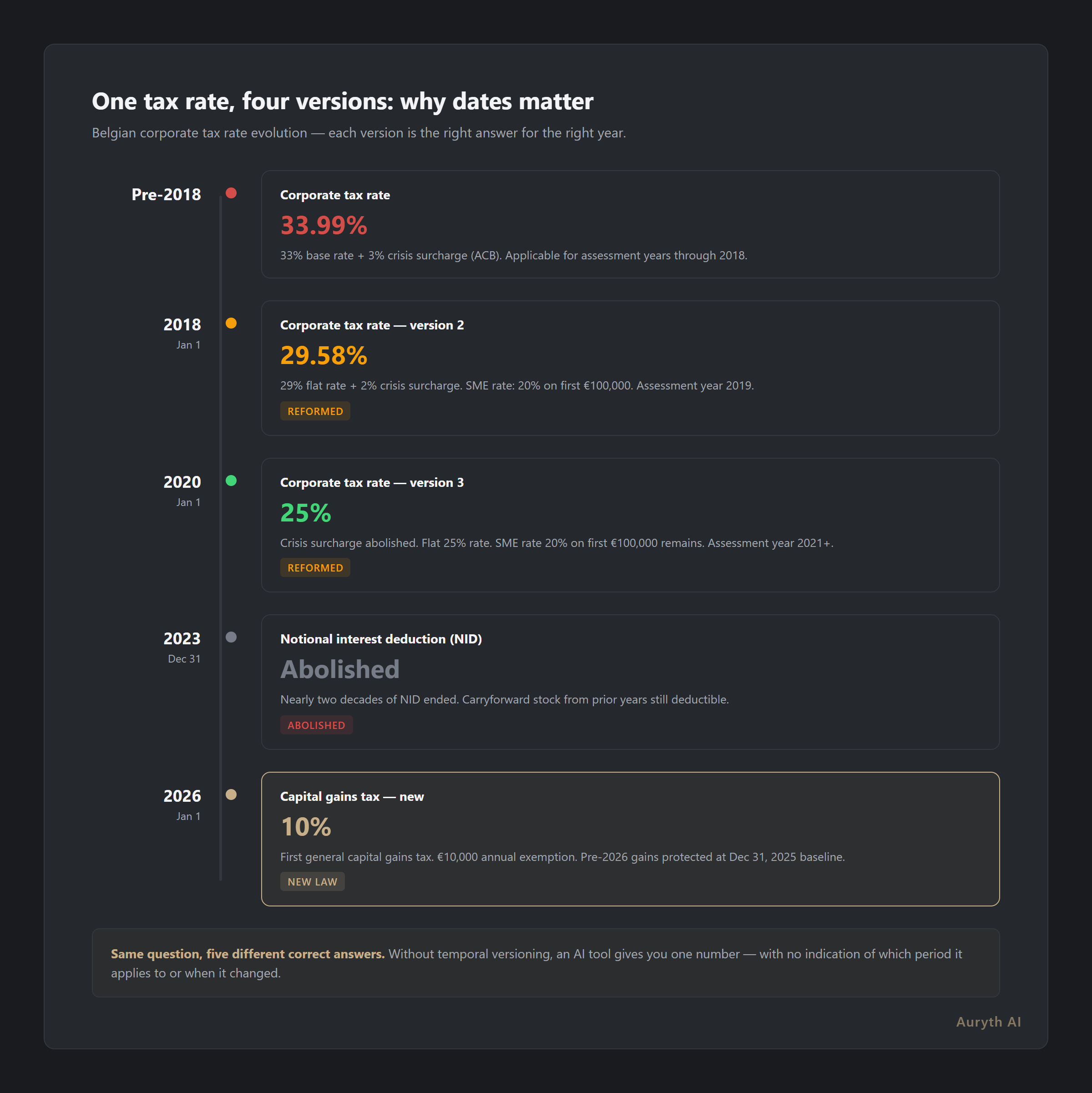

The Belgian corporate tax rate is 25%. It is also 29.58%. And 33.99%. All three are correct — depending on when you ask.

Before 2018: 33.99%. From 2018: 29.58% (29% flat rate plus crisis surcharge). From 2020: 25%. Three distinct rates in seven years, each affecting different assessment years, each the right answer for the right moment in time.

Ask a generic AI tool “what is the Belgian corporate tax rate?” and you will get one number. You will not be told which period it applies to. You will not be told that it was different three years ago. You will not be told that a client’s 2019 tax return uses a completely different rate than a 2024 filing.

This is the temporal versioning problem — and it affects every question in Belgian tax law.

What temporal versioning means

Temporal versioning is the ability to track multiple versions of the same legal provision over time and retrieve the correct version for a specific date or period.

Every piece of legislation has a lifecycle. It is enacted on one date, takes effect on another, gets amended on a third, and may be repealed on a fourth. A provision that exists today may not have existed last year. A rate that applies this year may not apply next year.

In a temporally versioned system, every provision carries metadata:

- effective_from — when the provision takes effect

- effective_to — when it stops applying (or “current” if still in force)

- assessment_year — for tax provisions, which assessment year(s) it covers

- amendment_chain — which prior version it replaced, and what replaced it

Without this metadata, a legal database is a snapshot. With it, it becomes a timeline.

The question is never just “what does the law say?” It is always “what did the law say when?”

Why Belgian tax law makes this especially hard

Belgian tax law changes constantly. The federal government passes program laws (programmawetten) at least twice per year — typically in June and December as part of the budget cycle. Additional laws, royal decrees, and circulars are published throughout the year.

In 2023-2024 alone, Belgian tax saw:

- Abolition of the notional interest deduction (December 2022 omnibus law, effective for taxable periods ending from December 31, 2023)

- Introduction of Pillar Two minimum taxation at 15% (Income Inclusion Rule from December 31, 2023; Undertaxed Profits Rule from December 31, 2024)

- Introduction of a 10% capital gains tax (effective January 1, 2026, with pre-2026 gains protected at December 31, 2025 baseline)

- Reform of regional inheritance tax in Flanders (2026) and Wallonia (2028) — same country, different effective dates

Each of these changes creates a new version of one or more legal provisions. Each version has different applicability rules. Each version is the correct answer — for its period.

The assessment year trap

Belgian tax adds an extra layer of complexity: the distinction between income year (inkomstenjaar) and assessment year (aanslagjaar). The assessment year is always the year after the income year — so assessment year 2026 covers income earned in 2025.

Tax law changes are often expressed as “applicable from assessment year X.” For a company with a fiscal year ending March 31, assessment year 2026 covers income from April 1, 2024 to March 31, 2025. For a company with a calendar fiscal year, it covers January 1 to December 31, 2025.

Same assessment year. Different calendar periods. Different applicable law.

A system that only tracks calendar dates will get this wrong. A system that understands the relationship between income year, assessment year, and fiscal year closing date will get it right.

What happens without temporal awareness

Without temporal versioning, three failure modes are common:

1. Serving current law for historical questions. A client asks about a transaction from 2019. The system returns the 2026 corporate tax rate (25%) instead of the 2019 rate (29.58%). The difference: 4.58 percentage points on the entire taxable base.

2. Serving repealed provisions as current. The notional interest deduction was a cornerstone of Belgian corporate tax planning for nearly two decades. It was abolished effective 2023 — but the carryforward stock from prior years remains deductible. A system without version tracking might either miss the abolition or miss the carryforward exception.

3. Missing transition rules. The new capital gains tax protects pre-2026 gains by using the December 31, 2025 value as the acquisition baseline. This is a transitional rule that only applies to contracts existing before the law took effect. Without temporal awareness, the system cannot distinguish between a contract opened in 2024 and one opened in 2027.

Each failure mode produces answers that look correct — they cite real legislation, use the right article numbers, apply the right logic — but for the wrong point in time.

The database lag problem

Even if a system intends to be current, there is a structural delay between legislation and availability:

- The Belgisch Staatsblad / Moniteur Belge publishes daily (electronic only since 2003)

- The legislative index is updated D+1 — one day after publication

- Consolidated full texts in databases can lag by 3 to 5 months for older provisions

This means a provision published today may appear as a raw amendment tomorrow but may not be reflected in consolidated texts for months. During that window, a full-text search on the consolidated version returns the old law, while the amendment exists only in the gazette.

A temporally aware system tracks both: the amendment as published, and the prior version it modifies — with a clear indication of which applies when.

How existing systems handle this

EUR-Lex (for EU legislation) offers consolidated versions that show the act as applicable at a specific point in time. Users can view all versions and compare changes. But these consolidated texts have no legal force — they are documentation only.

Jura (Wolters Kluwer Belgium) has included consolidated legislation since 2000, and now offers side-by-side comparison of law versions with differences highlighted.

Generic AI tools — ChatGPT, Perplexity, Claude — have none of this. Their training data has a knowledge cutoff. They cannot distinguish between current and former versions of a provision. They cannot tell you what the law said on a specific date. They do not know that the law they are citing was amended six months after their training data was compiled.

This is not a limitation that can be fixed with a larger model or better training. It is an architectural gap — the absence of temporal metadata in the system’s data layer.

The 2026 inflection point

The introduction of Belgium’s first general capital gains tax on January 1, 2026 creates the most significant temporal boundary in recent Belgian fiscal history.

Before 2026: no tax on capital gains from financial instruments (for private individuals). After 2026: 10% on realized gains above a €10,000 annual exemption. The acquisition value for pre-2026 contracts is fixed at the December 31, 2025 market value.

Every TAK 23 contract, every investment portfolio, every ETF position now has a temporal split: the gain before the cutoff date (not taxed) and the gain after (taxed at 10%). Any system that cannot distinguish “before January 1, 2026” from “after January 1, 2026” will miscalculate the taxable gain.

Add to this the regional inheritance tax reforms — Flanders from 2026, Wallonia from 2028, Brussels unchanged — and a single estate planning question now requires temporal precision across multiple jurisdictions with different reform timelines.

What temporal versioning requires architecturally

Building temporal versioning is not a feature toggle. It requires structural decisions at every layer:

Ingestion: Every document must be parsed for effective dates, amendment references, and repeal clauses. This goes beyond full-text indexing — it requires understanding the legislative structure of the document.

Storage: Every provision exists as a version chain, not a single record. Version N points to Version N-1 (what it replaced) and Version N+1 (what replaced it, if applicable). Each version carries its effective date range.

Retrieval: When a user asks a question, the system must determine the relevant time period — either explicitly stated or inferred from context — and retrieve only the provisions that were in force during that period.

Presentation: The output must indicate which version of the law it is citing, when that version took effect, and whether a newer version exists.

This is architecturally expensive. It is why most legal AI tools do not offer it. Full-text search on a current-state corpus is vastly simpler and cheaper than maintaining a temporally indexed version graph.

But for Belgian tax law — where the corporate tax rate changed three times in seven years, where a new capital gains tax creates a hard temporal boundary, where regional reforms take effect in different years — temporal precision is not optional. It is the difference between a correct answer and a correct answer for the wrong year.

Related articles

- What is authority ranking — and why your legal AI tool probably ignores it →

- What is confidence scoring — and why it’s more honest than a confident answer →

- Case study: TAK 23 — why one product needs five tax answers →

How Auryth TX applies this

Every provision in our system carries an effective date. When the corporate tax rate changed from 29.58% to 25%, we did not replace the old record — we added a new version linked to the prior one, with the effective date of the change.

When you ask Auryth TX a question, the system identifies the relevant time period and retrieves only the provisions that were in force during that period. If you ask about a 2019 transaction, you get the 2019 law. If you ask about a 2026 transaction, you get the 2026 law. If you ask about the capital gains tax, the system distinguishes between pre-2026 gains and post-2026 gains automatically.

Where a provision has been amended, the structured output shows the version chain — what the law said before, what it says now, and when the change took effect. This is not cosmetic. It is the difference between advice that is technically correct and advice that is correct for the client’s actual situation.

Every provision carries a date. We never confuse 2019 with 2026.

Sources: 1. PwC Tax Summaries. “Belgium — Corporate — Taxes on corporate income.” taxsummaries.pwc.com. 2. Deloitte Belgium. “Belgium tax reforms — The latest federal and regional tax measures.” deloitte.com/be. 3. PwC Belgium (2026). “Belgium’s comprehensive capital gains tax changes: key updates and implications starting January 2026.” 4. Bird & Bird (2023). “Belgium: New corporate tax measures in force as of 1 January 2023.” 5. European Forum of Official Gazettes. “Belgium — Official Journal.” op.europa.eu. 6. CMS Law-Now (2024). “Belgium’s regions pass new registration and inheritance tax rates.”