The future of tax research: what AI changes, what it doesn't, and what that means for your practice

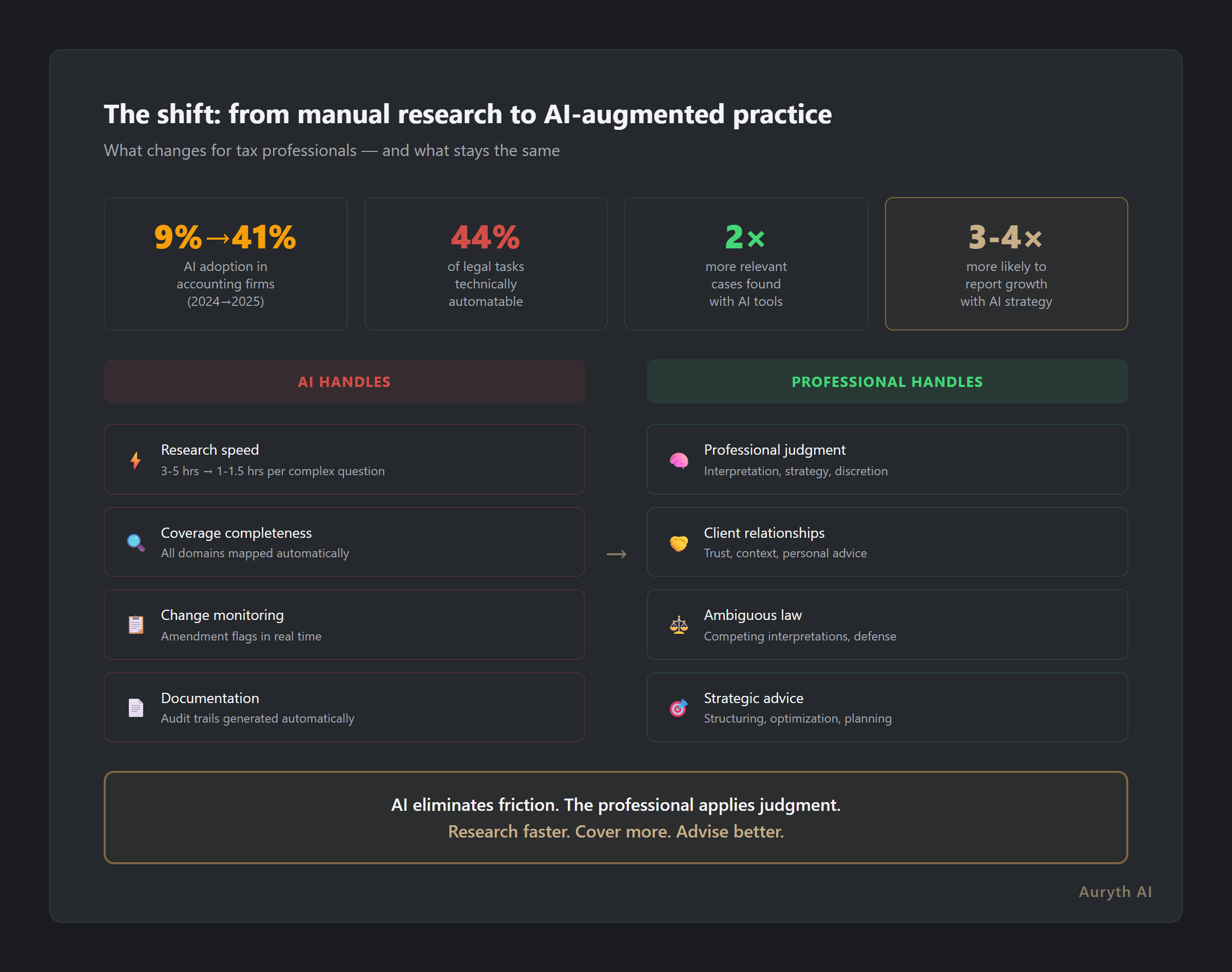

AI adoption in accounting firms surged from 9% to 41% in one year. McKinsey says 44% of legal tasks are technically automatable. The World Economic Forum lists bookkeeping among the fastest-declining roles. Here's what this actually means for Belgian tax professionals — and what it doesn't.

By Auryth Team

The numbers are stark. AI adoption among accounting firms surged from 9% in 2024 to 41% in 2025 — a nearly fivefold increase in twelve months. McKinsey’s November 2025 report found that 44% of legal tasks are technically automatable with existing AI. The World Economic Forum’s Future of Jobs 2025 report lists accounting and bookkeeping clerks among the fastest-declining roles globally.

These are not predictions about 2035. They describe what is happening right now.

But the headlines — “AI will replace lawyers” or “the end of the accounting profession” — fundamentally misread what the data actually shows. The shift is not replacement. It is restructuring. And the professionals who understand the difference will define the next decade of the Belgian tax profession.

What AI changes

There are tasks where AI already outperforms the traditional workflow. Not in theory — in measured, verified practice.

Research speed

A complex cross-domain Belgian tax question — the kind involving multiple federal and regional provisions, cross-references, and temporal verification — takes a professional 3-5 hours through traditional research. An AI system built for this workflow can reduce that to 1-1.5 hours by automating domain identification, parallel source retrieval, and regional comparison.

The international data supports this. Harvey power users report saving 36.9 hours per month. The Forrester study for LexisNexis found 2.5 hours saved per week for senior associates. Even at the conservative end, the time savings on complex research are measurable and consistent.

Coverage completeness

This is where the data gets interesting. Thomson Reuters found that lawyers using AI tools discovered twice as many relevant cases compared to manual research. LexisNexis reported that 85% of users found information they would not have found through manual review alone.

For Belgian tax, this is structural. A product like TAK 23 touches seven distinct tax domains. Most advisors cover three of those domains by default — the ones they know to look for. An AI system with a knowledge graph can map all seven automatically, including the Art. 19bis interaction that most advisors miss and the regional inheritance tax variations that depend on the client’s postal code.

The coverage gap is not about competence. It is about the limits of human attention in a system with three regions, two official languages, and constant legislative change.

Change monitoring

Belgian tax law changes at least twice per year through program laws, plus ad-hoc amendments throughout the year. The July 2025 program law modified the participation exemption, added exit tax provisions, and made the 6% demolition-reconstruction VAT rate permanent — all in a single omnibus bill.

Manually tracking which provisions in your areas of practice have been affected by each program law is structurally impractical. An AI system with temporal versioning can flag when a source you relied on has been superseded — before you give advice based on outdated law.

Routine queries

Simple lookups — current VAT rates, corporate tax rates, filing deadlines — can be answered instantly by AI without adding significant value over existing resources. But the compound effect is meaningful: if a professional handles 10-15 routine queries per day, eliminating even 30 seconds per query saves 5-7 minutes daily. Across a year, that is 20-30 hours recovered for higher-value work.

What AI does not change

The tasks that AI cannot perform are precisely the ones that make a tax professional valuable.

Professional judgment

AI retrieves and organizes. It does not advise. When a client asks “should I restructure as a management company?”, the answer depends on their specific financial situation, risk tolerance, family circumstances, future plans, and a dozen other factors that no AI system can evaluate.

Research consistently shows that AI struggles with “open texture” situations — cases where the law is ambiguous or uncertain and requires interpretive discretion. Belgian tax is full of these: the interaction between federal and regional rules, the application of anti-abuse provisions, the optimal timing of transactions across tax years.

An AI system can present the applicable provisions, flag the relevant exceptions, and show how different jurisdictions handle the same question. The professional decides what it means for this specific client.

Client relationships

Tax advice is personal. Clients do not want an algorithm to tell them their estate planning options — they want a professional who understands their family dynamics, their business history, and their relationship with risk. The trust that enables candid financial disclosure cannot be replicated by technology.

Strategic advice

The highest-value tax work — structuring international transactions, optimizing group holding arrangements, navigating regulatory change — requires creative problem-solving that operates beyond what any current AI architecture can do. Strategy involves synthesizing incomplete information, weighing incommensurable factors, and making judgment calls under uncertainty.

AI can accelerate the research that feeds strategic thinking. It cannot replace the thinking itself.

Interpretation of ambiguous law

Belgian tax law contains provisions that reasonable professionals interpret differently. When the law is genuinely ambiguous — and it frequently is — the AI can present the competing interpretations and the authorities supporting each one. But selecting which interpretation to present to the client, and defending that choice to the administration, requires professional expertise and accountability that technology cannot provide.

The augmentation thesis

The emerging evidence does not support either the “replacement” narrative or the “nothing will change” narrative. What the data shows is augmentation: the best professionals will use AI to work faster, cover more ground, and catch more exceptions — not to be replaced.

The Big Four are already demonstrating this model. EY launched its AI platform with 150+ specialized tax agents in 2025 — not to eliminate tax professionals, but to equip 80,000 of them with better tools. Big Four accounting graduate job adverts fell 44% year-over-year in 2024, but the remaining roles are higher-skilled and higher-paid. The “diamond model” — a thinner base of routine tasks with a wider middle of technical and advisory expertise — is replacing the traditional pyramid.

For Belgian tax practice, augmentation means:

- Broader dossiers. A professional who previously specialized in one domain can now efficiently research cross-domain questions, expanding their scope without sacrificing depth.

- Faster turnaround. Complex research that took a day can be completed in hours, allowing more dossiers per week without working longer hours.

- Higher confidence. Systematic retrieval reduces the risk of missing a critical provision — the exception you did not know to look for, the amendment you had not yet tracked, the regional variation you forgot to check.

- Better documentation. AI-generated research trails with sources, confidence levels, and version metadata create audit-ready documentation automatically.

New skills for the AI-augmented professional

The transition creates demand for competencies that did not exist five years ago:

Evaluating AI output. Not everything an AI system returns is correct. Stanford’s 2024 study found that even the best legal AI tools hallucinate 17-33% of the time — dramatically better than general-purpose models (58-82%), but far from infallible. The skill is not prompting; it is knowing what to verify and how to verify it efficiently.

Knowing when NOT to use AI. Some questions are too simple for AI (check the rate table). Others are too complex (restructure the client’s entire holding). Others involve confidential information that should not be entered into any external system. The OVB’s AI guidance is explicit: lawyers should not enter personal data into AI tools and must pseudonymize when possible.

Systematic verification. The value of AI research is not accepting its output — it is using its output as a structured starting point for professional verification. The professional reads the cited provisions, checks the effective dates, confirms the jurisdiction, and validates the logic. AI compresses the search; the professional validates the result.

Understanding AI limitations. A professional who understands that AI is strong on retrieval but weak on interpretation, strong on coverage but weak on judgment, will use the tool appropriately. One who treats AI output as a finished answer is exposed to the same errors the tool makes.

The competitive dynamic

The adoption curve is already steep. Firms with a clear AI strategy are 3-4 times more likely to report revenue growth and efficiency gains than those without one. Tech-forward firms are growing faster, reporting higher profitability, and attracting talent that demands modern tools.

In Belgium, this dynamic plays out through structural advantages:

Speed-to-advice. A professional using AI research completes a complex dossier in hours instead of days. For clients who need timely advice — an upcoming transaction, a filing deadline, a regulatory change — speed is a differentiator.

Coverage depth. A professional whose tool maps all seven applicable tax domains for a TAK 23 product provides more defensible advice than one who covers three domains manually. The coverage advantage is visible in the advice quality.

Change responsiveness. A professional whose tool flags when a cited provision has been amended by the latest program law catches the change before giving outdated advice. The alternative is relying on memory and manual monitoring — structurally unreliable in a system with twice-yearly legislative overhauls.

The Wolters Kluwer 2025 report warns that firms failing to develop an AI plan now could fall “irreparably behind within three years.” Whether or not that timeline proves exact, the direction is clear: the gap between AI-equipped and AI-absent practices will widen, not narrow.

The liability question

This is the dimension that most professionals underestimate. As AI research tools become standard practice, the question shifts from “is it safe to use AI?” to “is it safe not to?”

The professional standard of care is not static. It evolves with available technology. When electronic filing replaced paper filing, not adopting it eventually became a failure to meet the standard of care. When legal databases replaced physical libraries, manual-only research became insufficient.

AI-assisted research is on the same trajectory. The OVB already recognizes AI as a legitimate supporting tool. The ABA issued Formal Opinion 512 on lawyers’ use of generative AI. Multiple state bars have published formal guidance. The direction is normalization, not prohibition.

The risk that should concentrate attention is twofold. Over-reliance on AI — using unverified AI output as finished work product — has already generated hundreds of documented cases of AI-driven legal errors since 2023. But the inverse risk is growing: under-coverage because the professional did not use available tools to check for provisions they would not have found manually.

The professional who discovers relevant but overlooked provisions after using an AI tool has a clear argument that they met the standard of care. The professional who missed those same provisions because they relied solely on manual research faces an increasingly uncomfortable question.

What this means for Belgian practice

Belgium’s tax system — with its three regions, two official languages, constant legislative change, and high structural complexity — is precisely the environment where AI augmentation provides the most value. The professional who manually researches a cross-domain question in this system is fighting the complexity with a tool designed for simpler environments.

The ITAA represents over 16,000 accounting and tax professionals in Belgium. There are approximately 18,740 attorneys across the Flemish, French, and German-speaking bars. Some fraction of these professionals specialize in or regularly encounter tax questions. All of them face the same structural challenge: a legal system that is more complex, more fragmented, and faster-changing than any individual can comprehensively track.

The professionals who adopt AI research tools will not stop being professionals. They will become faster, more thorough, and more defensible professionals. The ones who do not adopt will not stop being competent — but they will increasingly struggle to match the coverage, speed, and documentation quality of their AI-augmented peers.

The future of tax research is not AI replacing judgment. It is AI eliminating the friction that prevents judgment from being applied to the full scope of the question.

Related articles

- “I don’t trust AI for tax advice” — and you’re right. Here’s why you should try it anyway. →

- How much time does tax AI actually save? An honest estimate →

- How to evaluate a legal AI tool: 10 questions that actually matter →

How Auryth TX applies this

Auryth TX is designed for the augmentation model — not to replace the professional, but to handle the structural friction that slows down research, narrows coverage, and creates blind spots.

The domain radar maps every applicable tax regime automatically, so the professional does not need to know in advance which domains are relevant. The regional comparison presents all three regions side by side, so coverage gaps between Flanders, Wallonia, and Brussels are eliminated by default. The temporal versioning ensures every provision is current, with amendment flags when the law has changed since the last research.

The result: the professional spends their time on interpretation, judgment, and client advice — not on searching, cross-referencing, and verifying temporal accuracy. The AI handles the retrieval. The professional handles the decision.

At €99/month, the tool costs less than the billable value of a single complex dossier handled faster. The ROI is not in replacing the professional — it is in freeing the professional to do the work that only a professional can do.

Research faster. Cover more. Advise better.

Sources: 1. Wolters Kluwer (2025). “Future Ready Accountant Report.” wolterskluwer.com. 2. McKinsey (2025). “Agents, Robots, and Us: Skill Partnerships in the Age of AI.” 3. World Economic Forum (2025). “Future of Jobs Report 2025.” 4. Stanford Law School (2024). “Hallucination-Free? Assessing the Reliability of Leading AI Legal Research Tools.” 5. OVB (2025). “AI-richtlijnen voor advocaten.” ovb.be. See also: Alice.law (2025). “AI guidelines for lawyers in Belgium and the Netherlands.” 6. ABA (2024). “Formal Opinion 512: Lawyers’ Use of Generative AI.” americanbar.org. 7. Avalara (2025). “AI in Finance and Tax Compliance Report.” 8. EY (2025). “EY.ai Agentic Platform Launch.” ey.com.