What is chunking — and why it's the invisible foundation of legal AI quality

Before your legal AI tool can answer a question, it has to cut the law into pieces. The way it cuts determines whether the answer includes the exception that changes everything — or misses it entirely.

By Auryth Team

Every conversation about legal AI quality eventually arrives at the same place: retrieval. Does the system find the right sources? Does it return the relevant provisions? Does it catch the exception buried in the third alinea?

But before retrieval can happen, something more fundamental must occur. The system has to decide how to cut the legal corpus into pieces — pieces small enough to search, large enough to remain meaningful. This process is called chunking, and it is the single most underappreciated factor in legal AI quality.

Get it wrong, and the best retrieval model in the world will return incomplete answers. Get it right, and even a modest system can produce defensible results.

Why AI needs chunks at all

Modern language models have increasingly large context windows — both Claude and GPT-4.1 now support up to a million tokens. You might think this eliminates the need for chunking entirely: just feed the AI the full legal code and ask your question.

This does not work for three reasons.

Attention dilution. Research consistently shows that LLMs struggle with information placed in the middle of very long inputs — a phenomenon known as the “lost in the middle” effect. The model attends strongly to the beginning and end of the text but weakens in between. For a legal corpus where the critical exception may sit at paragraph 47 of a 200-paragraph input, this is not a theoretical concern.

Retrieval precision. A Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) system does not feed the entire corpus to the model. It searches the corpus for the most relevant pieces, retrieves the top results, and feeds only those to the model. This requires the corpus to be divided into searchable units — chunks. The quality of these chunks determines the quality of what the model sees.

Cost and latency. Processing a million tokens costs €2–15 per query depending on the model. For a tax research tool that handles dozens of queries per day, context-stuffing the full corpus is not economically viable.

Chunking is not a workaround for limited context windows. It is an architectural requirement for retrieval-based systems — and every serious legal AI system is retrieval-based.

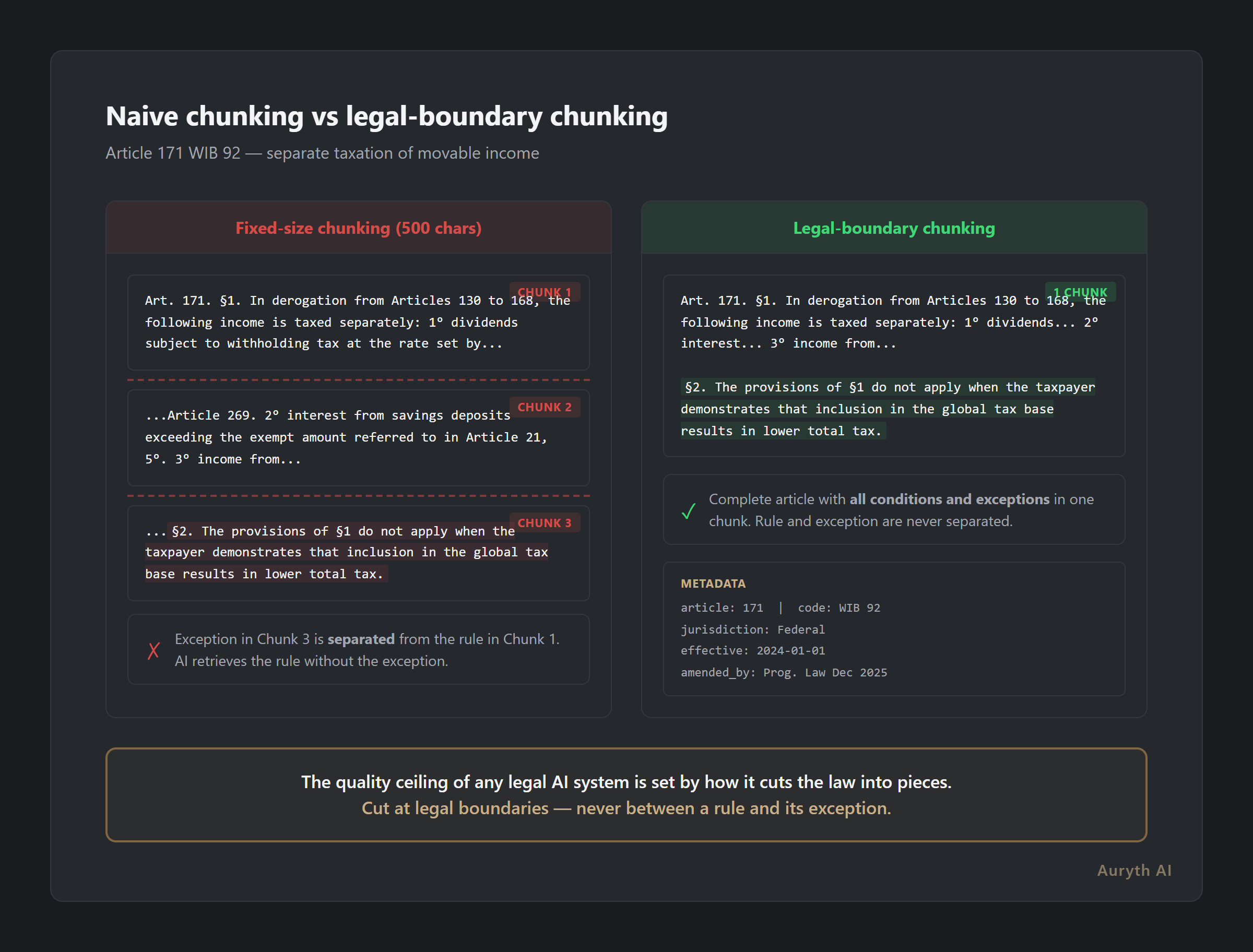

Naive chunking: the wrong way to cut

The simplest approach is fixed-size chunking: split the text every 500 characters or 200 tokens, regardless of content.

This is how many general-purpose AI tools handle documents. It works well enough for blog posts, customer emails, and product manuals — text where the meaning of one paragraph does not critically depend on the next.

For legal text, it is catastrophic.

Consider Article 171 of the Belgian Income Tax Code (WIB 92), which governs separate taxation of movable income. A simplified structure:

Article 171. §1. In derogation from Articles 130 to 168, the following income is taxed separately:

1° dividends [conditions]…

2° interest [conditions]…

[multiple numbered categories with specific rates]

§2. The provisions of §1 do not apply when the taxpayer demonstrates that inclusion in the global tax base results in a lower total tax burden.

A naive chunker splitting at 500 characters might produce:

Chunk 1: “Article 171. §1. In derogation from Articles 130 to 168, the following income is taxed separately: 1° dividends subject to…” (cuts mid-provision)

Chunk 2: “…a withholding tax at the rate set by Article 269. 2° interest from…” (continues from nowhere)

Chunk 3: ”…§2. The provisions of §1 do not apply when the taxpayer demonstrates that inclusion in the global tax base…” (the exception, now orphaned from its context)

An AI that retrieves only Chunk 1 will state that dividends are taxed separately — period. It will miss that the taxpayer can opt to include them in global income if that results in lower tax. This is not a nuance. For a client with low other income, this exception changes the entire advisory outcome.

The “behoudens” problem

Belgian legal text has a characteristic structure that makes naive chunking especially dangerous. Provisions regularly follow a pattern:

General rule → behoudens (except) → tenzij (unless) → mits (provided that)

Each qualifier narrows or reverses the general rule. The legal meaning of any provision depends on the complete chain — rule plus all its qualifications.

When a fixed-size chunker splits this chain, the general rule appears absolute. The AI sees “dividends are taxed separately at 30%” without seeing “except when the global tax base would result in lower taxation” or “unless the participation exemption applies.”

This is not hallucination in the technical sense. The AI is accurately reproducing what it was given. The failure happened upstream, in chunking, where the complete provision was sliced into fragments that destroyed its legal meaning.

Legal-boundary chunking: cutting at the joints

The alternative is to chunk at legal boundaries — the structural divisions that the legislator actually intended.

Belgian tax law follows a hierarchical structure:

Code (WIB 92, BTW Code, VCF)

└─ Title (Titel I: Inkomstenbelastingen)

└─ Chapter (Hoofdstuk III: Vennootschapsbelasting)

└─ Section (Afdeling II: Belastbare grondslag)

└─ Article (Artikel 215)

└─ Paragraph (§1, §2, §3)

└─ Alinea (lid 1, lid 2)

└─ Numbered item (1°, 2°, 3°)Legal-boundary chunking respects this hierarchy. The default unit is the article — the fundamental building block of codified law. Each article addresses a distinct legal concept and is designed to be self-contained (though it may reference other articles).

Short articles like Article 1 WIB 92 (“A tax on total income is levied…”) fit easily into a single chunk with room to spare.

Medium articles like Article 215 WIB 92 (corporate tax rates, SME reduced rate, qualifying conditions) fill one chunk with all conditions intact.

Long articles with dozens of paragraphs and numbered items may exceed practical chunk limits. For these, the system splits at paragraph (§) boundaries, preserving complete semantic units. If paragraphs are still too long, it splits at alinea boundaries — but never mid-sentence, never mid-clause, never between a rule and its exception.

The Flemish Tax Code (VCF) adds an extra layer of structural precision with its distinctive hierarchical numbering: Article 2.10.4.0.1 encodes Title 2, Chapter 10, Section 4 directly in the article number. This built-in structure map makes legal-boundary chunking particularly clean.

What each chunk carries with it

A text fragment without metadata is a fragment without context. In legal AI, context is everything.

Every chunk in a properly designed system carries identification metadata:

- Article number and code reference — “Article 215 WIB 92” or “Article 2.7.1.0.3 VCF”

- Jurisdiction — Federal, or regional (Flanders, Wallonia, Brussels)

- Effective dates — When this version of the provision entered into force and, if applicable, when it was superseded

- Amendment history — Which program law last modified this provision, and what changed

- Cross-references — Which other articles this provision cites, and which articles cite it

- Authority level — Primary legislation, royal decree, circular, or administrative ruling

This metadata transforms retrieval from “find text that looks similar to the question” into “find the current, authoritative provision from the correct jurisdiction that applies to the client’s specific time period.”

Without it, the system might retrieve a 2019 version of Article 215 showing a 29.58% corporate tax rate — technically accurate text, but wrong for any question about the current regime.

How chunk quality cascades through the system

The retrieval pipeline operates as a chain:

Chunking → Embedding → Retrieval → Reranking → Answer generation

Each stage depends on the output of the previous one. Poor chunking propagates errors through every subsequent stage.

Embedding converts each chunk into a mathematical vector. If the chunk is a sentence fragment that ends mid-clause, the embedding captures an incomplete thought — and will match against the wrong queries.

Retrieval searches for chunks whose embeddings are most similar to the question. If the critical exception was chunked separately from the rule, the retrieval may return the rule without the exception — or the exception without the rule.

Reranking re-evaluates the top results with a more sophisticated model. It can catch some chunking errors by recognizing that a result is incomplete. But it cannot reconstruct information that was split across chunks it never sees.

Answer generation synthesizes the retrieved chunks into a response. If it receives five well-chunked, complete provisions with metadata, it can produce a defensible answer with proper citations. If it receives five text fragments with no article numbers and no effective dates, even the most capable model will produce an answer that looks confident but cannot be verified.

This is the fundamental insight: the quality ceiling of any RAG-based legal AI system is set by its chunking strategy. No amount of model sophistication downstream can compensate for structural destruction upstream.

What this means for practitioners

When evaluating a legal AI tool, the chunking strategy is not a technical detail to skip over. It is the architectural decision that determines whether the tool can reliably return complete legal provisions with their exceptions, conditions, and temporal context.

Three questions worth asking:

-

Does the tool preserve complete articles with all conditions and exceptions? If the answer involves how the tool “summarizes” provisions or “extracts key points,” the chunking may be destroying the legal structure rather than preserving it.

-

Does each result carry metadata — article number, jurisdiction, effective date? If results show text without clear provenance, the system likely chunks without metadata. This makes verification and citation impossible.

-

Can the tool distinguish between current and historical provisions? If the system returns outdated versions without flagging them, the temporal metadata is missing — a chunking and indexing failure.

The irony of chunking is that when it works well, it is invisible. The user simply sees correct, complete, well-cited answers. The architecture that made those answers possible — the careful cutting, the metadata preservation, the boundary detection — operates entirely behind the scenes.

When it works poorly, the failures are also invisible — until a client relies on advice that missed the exception in the third alinea.

Related articles

- What is RAG — and why it’s the only architecture that makes legal AI defensible →

- What is authority ranking — and why your legal AI tool probably ignores it →

- What is confidence scoring — and why it’s more honest than a confident answer →

How Auryth TX applies this

Auryth TX chunks at legal boundaries — articles, paragraphs, and alinea’s — never at arbitrary character or token limits. The WIB 92, BTW Code, VCF, and regional codes are each parsed according to their specific structural conventions. The VCF’s hierarchical numbering, the WIB’s paragraph-and-alinea structure, the BTW Code’s article-and-royal-decree organization — each requires a different parsing approach, and each gets one.

Every chunk carries its full provenance: article number, code reference, jurisdiction, effective date range, amendment chain, and cross-references to related provisions. When the system retrieves Article 215 WIB 92, it retrieves the current version — with metadata flagging when it was last amended by the July 2025 program law and what changed.

The result: when the system says “dividends are taxed separately under Article 171 WIB 92,” the complete provision is behind that answer — including §2’s exception for taxpayers who benefit from global inclusion. The exception is not in a different chunk. It is right there, because the system never separated the rule from its qualifications.

Chunking at legal boundaries. Every provision complete. Every exception preserved.

Sources: 1. Liu, N.F. et al. (2024). “Lost in the Middle: How Language Models Use Long Contexts.” Transactions of the ACL, 12, 157-173. 2. ResearchGate (2024). “Legal Chunking: Evaluating Methods for Effective Legal Text Retrieval.” 3. Milvus (2025). “Best practices for chunking lengthy legal documents for vectorization.” 4. Weaviate (2024). “Chunking Strategies for RAG.” 5. Elvex (2026). “Context Length Comparison: Leading AI Models in 2026.”