What is reranking — and why it's the difference between finding documents and finding answers

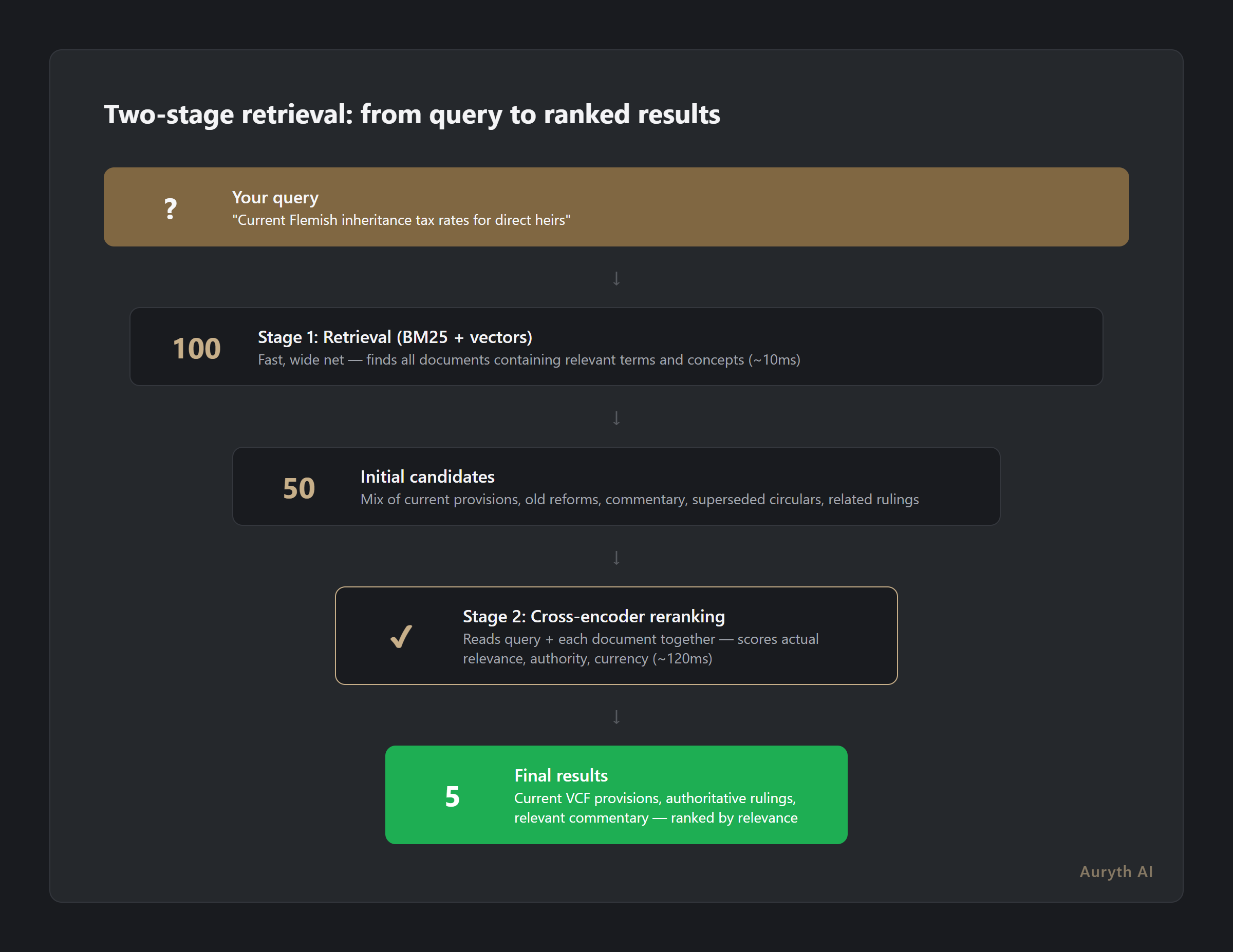

First-stage retrieval finds 100 matches. Reranking identifies the 5 that actually answer your question. Here's why that distinction matters for legal AI.

By Auryth Team

Your AI tool found 100 documents matching your query. It showed you 5. How did it decide which 5?

This question matters more than most professionals realise. The difference between the document that contains the right keywords and the document that actually answers your question is the difference between retrieval and reranking — and it’s where most legal AI tools cut corners.

Benchmarks from Elastic’s semantic reranker study show the gap clearly: on the BEIR benchmark suite, reranking BM25 results improves relevance by an average of 39%. On Natural Questions specifically, the improvement reaches 90%. The technology that sits between “I found matching documents” and “here are the relevant ones” isn’t a nice-to-have — it’s the quality layer that makes AI output trustworthy.

The right words, wrong answer problem

Consider a Belgian tax professional searching for the current rules on inheritance tax in the Flemish Region. First-stage retrieval — whether keyword-based (BM25) or semantic — casts a wide net. It returns every document that discusses Flemish inheritance tax: the current VCF provisions, a 2018 reform proposal, a superseded 2015 circular, academic commentary from 2020, and a court ruling that has since been overturned.

All of these documents contain the right words. Only some of them contain the right answer.

This is the right words, wrong answer problem. A document about the 2018 reform of Flemish inheritance tax rates and a document about the current 2024 rates both match the same query. But only one answers the question “what are the current rates?” First-stage retrieval cannot tell the difference because it evaluates queries and documents separately.

How reranking works: reading query and document together

The key insight behind reranking is architectural. First-stage retrievers — both keyword (BM25) and semantic (bi-encoders) — encode queries and documents independently. The query becomes a vector. Each document becomes a vector. Similarity is computed by comparing vectors, without the system ever “reading” the query and document side by side.

A cross-encoder reranker does the opposite. It takes the query and a candidate document, concatenates them, and passes both through a transformer model that can attend to every token in both texts simultaneously. This means the reranker understands not just “this document mentions inheritance tax” but “this document answers this specific question about current Flemish inheritance tax rates.”

The tradeoff is speed versus precision. Bi-encoders process millions of documents in milliseconds because document vectors are precomputed. Cross-encoders need a fresh forward pass for each query-document pair — making them impractical for searching entire corpora, but ideal for re-evaluating a shortlist of 50–100 candidates. The two-stage pipeline combines both: cast a wide net fast, then evaluate the catch carefully.

A search engine that finds documents containing the right words is a database. A search engine that finds documents answering the right question is a research tool.

What the benchmarks show

The empirical evidence is consistent across studies:

| Stage | nDCG@10 (BEIR average) | What it means |

|---|---|---|

| BM25 only | 0.426 | Keyword matches — relevant terms, imprecise ranking |

| Bi-encoder only | ~0.45 | Semantic matches — better concepts, still imprecise |

| BM25 + reranker | 0.565 | +39% — documents actually answering the query rise to the top |

On specific tasks, the gains are larger: +90% on Natural Questions, +85% on MS MARCO. In RAG systems, cross-encoder reranking improves answer accuracy by an average of 33% across eight benchmarks, with complex multi-hop queries seeing improvements of 47–52% (Nogueira & Cho, 2019; Thakur et al., 2021).

The pattern is clear: the more complex the query, the more reranking helps. Simple factual lookups (“what is the corporate tax rate?”) benefit modestly. Cross-domain questions (“how does the interaction between Art. 19bis WIB and the TAK 23 insurance tax affect a specific investment structure?”) benefit dramatically.

Why legal search demands more than generic reranking

Generic rerankers treat all documents as equal. A blog post and a Supreme Court ruling get the same treatment. For general web search, this works. For legal research, it’s a critical gap.

Legal-domain reranking needs to incorporate three signals that generic models ignore:

Authority hierarchy. A ruling from the Hof van Cassatie (Court of Cassation) should outrank a lower court decision on the same point of law. A statutory provision should outrank commentary about that provision. Generic rerankers don’t know that constitutions outweigh circulars.

Temporal validity. A 2024 ruling on Flemish inheritance tax rates supersedes a 2019 ruling on the same question. Generic rerankers see both as equally relevant keyword matches. Domain-aware reranking deprioritises superseded sources.

Jurisdictional relevance. For a question about Flemish inheritance tax, Flemish VCF provisions are binding authority. Federal WIB provisions and Walloon C.Succ. provisions are context. Generic rerankers cannot make this distinction.

Harvey AI’s BigLaw Bench found that domain-optimised legal retrieval identifies up to 30% more relevant content than standard reranking from providers like OpenAI, Voyage, and Cohere. Generic reranking is necessary but not sufficient for legal work.

The honest limitation: bounded recall

Reranking has one structural limitation worth understanding. It can only reorder documents that the first stage already retrieved. If a relevant document didn’t make it into the initial candidate set — because the query terms didn’t match or the embedding similarity was too low — no amount of reranking will surface it.

This is why hybrid search (combining keyword and semantic retrieval) matters as the first stage. The wider the initial net, the more material the reranker has to work with. Reranking doesn’t replace good retrieval — it amplifies it.

Common questions

What is the difference between a bi-encoder and a cross-encoder?

A bi-encoder encodes query and document separately into fixed-size vectors, then compares them via cosine similarity. Fast but imprecise — it compresses all meaning into a single vector. A cross-encoder reads query and document together through a shared transformer, attending to every token in both. Slower but far more accurate — it understands the relationship between the specific query and the specific document.

Does reranking add noticeable latency?

For a shortlist of 50–100 candidates, cross-encoder reranking adds roughly 100–150 milliseconds. Combined with first-stage retrieval (under 50ms), total response time stays well under one second. The user doesn’t notice the difference, but the quality improvement is substantial.

Can reranking eliminate hallucinations in legal AI?

Not directly, but it dramatically reduces them. Hallucinations often occur when the LLM receives marginally relevant documents and has to fill gaps with generated content. When reranking ensures the most relevant, authoritative documents reach the generation layer, the LLM has less reason to fabricate — and the source citations are more likely to support the actual answer.

Related articles

- How hybrid search works — and why your legal AI tool probably uses only half the equation → /en/blog/hybride-zoektechnologie-en/

- What is authority ranking — and why your legal AI tool probably ignores it → /en/blog/authority-ranking-juridische-ai-en/

- What is RAG — and why it’s the only architecture that makes legal AI defensible → /en/blog/wat-is-rag-en/

How Auryth TX applies this

Auryth TX uses a two-stage retrieval pipeline with domain-specific reranking. The first stage combines BM25 keyword matching with dense vector retrieval to maximise recall. The reranking stage evaluates each candidate against the actual query, incorporating authority hierarchy — statutory provisions rank above commentary, higher courts above lower courts — and temporal validity, so superseded sources are deprioritised automatically.

This means the results a professional sees aren’t just relevant by keyword match. They’re relevant by meaning, ranked by authority, and current by law. The reranker doesn’t just find documents containing the right words. It finds the documents that answer the question.

Sources: 1. Nogueira, R. & Cho, K. (2019). “Passage Re-ranking with BERT.” arXiv preprint. 2. Thakur, N. et al. (2021). “BEIR: A Heterogeneous Benchmark for Zero-shot Evaluation of Information Retrieval Models.” NeurIPS 2021. 3. Khattab, O. & Zaharia, M. (2020). “ColBERT: Efficient and Effective Passage Search via Contextualized Late Interaction over BERT.” SIGIR ‘20. 4. Pipitone, N. & Houir Alami, G. (2024). “LegalBench-RAG: A Benchmark for Retrieval-Augmented Generation in the Legal Domain.” arXiv preprint.