5 Belgian tax questions where generic AI is guaranteed to fail

These aren't trick questions. They're routine queries any tax professional faces. But they expose five architectural blind spots that no general-purpose AI can fix with a better prompt.

By Auryth Team

We tested ChatGPT, Copilot, and Gemini on five Belgian tax questions that any professional might ask during an ordinary workday. Not edge cases. Not trick questions. The kind of queries you’d fire off while reviewing a client file.

All five produced confident, well-structured answers. All five were wrong — or dangerously incomplete. And the failures weren’t random. Each one exposes a different architectural limitation that no prompt engineering can fix.

If you’re using generic AI for tax research, these are the questions you need to understand. Not because they’re the only failures — but because they represent the five structural categories of failure that repeat across every query.

1. The temporal trap

The question: “What was the Belgian corporate tax rate for SMEs with taxable income up to €100,000 in the 2020 assessment year?”

What generic AI says: “The SME rate is 20% on the first €100,000 of taxable income under Art. 215, paragraph 2 WIB 92.” Confident. Clear. Wrong for the period asked.

What actually happened: The reduced SME rate was 20.4% for assessment year 2020 (income year 2019), part of the transitional rates during the corporate tax reform. The 20% rate only applies from assessment year 2021 onward. The AI retrieves the current rate and projects it backward — because it has no concept of temporal versioning.

Why this fails architecturally: Generic AI models have a single knowledge snapshot. They don’t maintain temporal versions of legal provisions. When you ask about a historical period, the model has no mechanism to retrieve the law as it was at that point in time. It gives you what it “remembers” — which is usually the most recent version it was trained on.

What it costs you: An incorrect rate in a tax return triggers an administrative correction at best, a penalty at worst. For a professional, it’s also a reputational risk — the kind of error that makes clients question your attention to detail.

2. The regional confusion

The question: “What is the inheritance tax rate in Brussels for an inheritance of €300,000 received by a nephew?”

What generic AI says: It typically produces a rate table — but mixes Flemish and Brussels rates, or gives only one region’s rates without specifying which. Several models we tested gave the Flemish rate schedule (which uses different brackets and thresholds) while claiming to answer about Brussels.

What actually happened: Brussels applies its own rate schedule for category “between brothers and sisters” and “between uncles/aunts and nephews/nieces,” with different brackets than Flanders or Wallonia. The rate for a nephew on €300,000 in Brussels differs from Flanders by several thousand euros.

Why this fails architecturally: Belgium has three tax regions with diverging inheritance tax regimes. Generic AI treats Belgium as a single jurisdiction — or worse, cherry-picks provisions from whatever source its vector search finds first. It has no jurisdiction tagging on its training data and no mechanism to distinguish Flemish, Brussels, and Walloon rules when they use similar terminology.

What it costs you: Advising a Brussels client based on Flemish rates isn’t just inaccurate — it’s advising under the wrong legal framework entirely. The client relies on your number. If it’s wrong, the liability is yours.

3. The exception chain

The question: “Is there an exception to the general anti-abuse provision of Art. 344 §1 WIB 92 for operations that have been specifically approved by advance ruling?”

What generic AI says: Most models acknowledge Art. 344 and describe the general anti-abuse rule, but miss the critical nuance: the relationship between Art. 344 §1 (general anti-abuse), specific anti-abuse provisions (like Art. 344 §2), and the role of advance rulings (DVB) in providing legal certainty on specific operations.

What actually happened: The interaction between Art. 344 §1 WIB 92, the specific anti-abuse provisions, and the Dienst Voorafgaande Beslissingen (DVB) involves an exception-to-the-exception chain. A DVB advance ruling on a specific operation doesn’t automatically immunize it from Art. 344 §1 — but the analysis depends on whether the ruling specifically addressed the anti-abuse question and on the material facts presented.

Why this fails architecturally: Legal reasoning often involves chains of exceptions, where provision A has exception B, which itself has exception C. Generic AI treats each provision as an independent text chunk. It doesn’t model the logical relationships between them — the “except when” and “notwithstanding” and “without prejudice to” chains that define how provisions actually interact.

What it costs you: Anti-abuse analysis is among the highest-stakes tax work. An incomplete analysis that misses an exception — or an exception to an exception — can mean the difference between a structure that survives audit and one that doesn’t.

4. The cross-domain blindspot

The question: “What are all the tax implications of a Belgian resident converting a distributing ETF to an accumulating ETF?”

What generic AI says: It typically covers the TOB (tax on stock exchange transactions) implications — sometimes correctly — but misses most of the other domains. The answers we received covered 1-2 of the 5 relevant tax domains.

What actually happened: This operation touches at least five distinct tax domains:

- TOB — transaction tax on the sale of the distributing fund and purchase of the accumulating fund

- Art. 19bis WIB 92 — taxation of the “interest component” on exit from a debt fund if >10% in debt instruments

- Income tax — treatment of any realized capital gain (ordinary vs. speculation vs. professional)

- Withholding tax — treatment of any accrued dividend at the point of conversion

- Reporting obligations — foreign account reporting if the accumulating fund is held abroad

Why this fails architecturally: Generic AI processes your question as a single query against a flat text index. It has no concept of tax domain boundaries. It can’t systematically traverse from TOB to income tax to withholding tax to reporting obligations — because its retrieval mechanism doesn’t know these domains exist as separate, interrelated areas. Purpose-built systems with domain taxonomy can trigger multi-domain retrieval and flag which domains were covered and which weren’t.

What it costs you: Advising a client on a fund conversion while missing three of five tax implications isn’t partial advice — it’s advice that creates a false sense of completeness. The client assumes you’ve covered everything. You assumed the AI covered everything. Nobody checked.

5. The staleness problem

The question: “Is the Fisconetplus circular of 15 March 2023 on the tax treatment of cryptocurrency staking rewards still in force?”

What generic AI says: Models trained before a certain date will either confirm the circular exists or fabricate one. None can tell you whether it’s been superseded, withdrawn, or modified by subsequent administrative positions.

What actually happened: Administrative circulars and guidance evolve. They get superseded by new circulars, modified by court decisions, or rendered partially obsolete by legislative changes. A circular from 2023 may or may not reflect the current administrative position in 2026 — and the only way to know is to check whether subsequent positions have been issued.

Why this fails architecturally: Generic AI has no concept of document lifecycle. It doesn’t track which circulars have been superseded, which rulings have been overturned, or which provisions have been amended. Its knowledge is a snapshot — and it can’t tell you where that snapshot is stale. Purpose-built systems with temporal metadata and supersession tracking can flag when a source may no longer reflect current law.

What it costs you: Advising based on a superseded circular is advising based on law that no longer exists. The professional liability implications are straightforward.

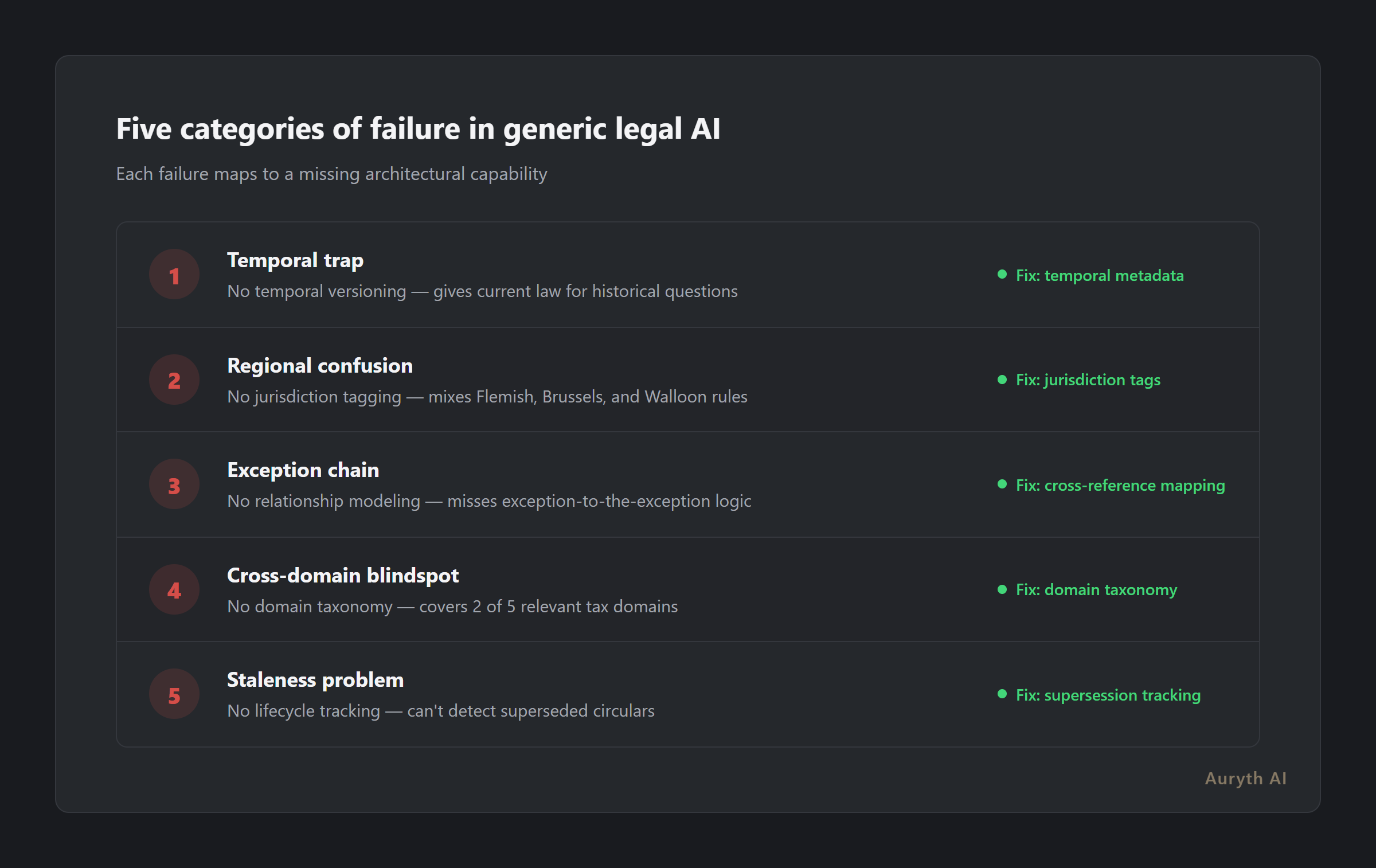

The pattern

These five failures aren’t bugs that will be fixed in GPT-6 or the next model release. They’re structural consequences of how generic AI processes text:

- No temporal versioning → wrong historical answers

- No jurisdiction tagging → regional confusion

- No logical relationship modeling → broken exception chains

- No domain taxonomy → incomplete cross-domain coverage

- No document lifecycle tracking → stale source reliance

Each failure maps to an architectural capability that general-purpose models don’t have — and can’t develop through better training alone. These require purpose-built search infrastructure, structured legal corpora, and domain-specific retrieval pipelines.

The question isn’t whether generic AI is “getting better.” It is. The question is whether the architecture can support professional-grade tax work. These five tests say no.

Related articles

- I asked ChatGPT and Auryth the same Belgian tax questions — here’s what happened

- AI hallucinations: why ChatGPT fabricates sources (and how to spot it)

- What is RAG — and why it’s not enough for legal AI on its own

How Auryth TX handles these five questions

These five failure categories are exactly what Auryth TX’s search-RAG fusion architecture was built to address:

-

Temporal — Every provision in our corpus carries temporal metadata. When you ask about assessment year 2020, the system retrieves the version of the law that applied in that period — not today’s version.

-

Regional — Jurisdiction tags on every document. A Brussels inheritance question retrieves Brussels rates from the Brussels tax code. Flemish provisions are excluded unless you explicitly ask for a comparison.

-

Exception chains — Cross-reference mapping between provisions. When Art. 344 §1 is retrieved, the system also retrieves the provisions that modify, limit, or extend it — and presents the relationship structure.

-

Cross-domain — Domain taxonomy triggers multi-domain retrieval. An ETF conversion question systematically traverses TOB, income tax, withholding tax, Art. 19bis, and reporting obligations — and flags which domains were covered.

-

Staleness — Supersession tracking and temporal validation. When you ask about a 2023 circular, the system checks whether subsequent administrative positions have been issued.

These aren’t features we added on top of a chatbot. They’re the architectural foundation of the system.

Test these five questions yourself — join the waitlist →

Sources: 1. Belgian Income Tax Code (WIB 92), Art. 215, Art. 344, Art. 19bis. 2. Brussels-Capital Region Inheritance Tax Code, Art. 48-54. 3. Magesh, V. et al. (2025). “Hallucination-Free? Assessing the Reliability of Leading AI Legal Research Tools.” Journal of Empirical Legal Studies.