Behind the scenes: how a law change flows through a legal AI system

When Belgium's programme law amends 47 provisions overnight, what happens inside the AI tool you rely on? A transparent look at the ingestion pipeline.

By Auryth Team

The programme law was voted on a Thursday. It amended 47 provisions across six codes — income tax, VAT, social security, corporate law, regional incentives, and inheritance tax. By Friday morning, the old law was history. By Monday, professionals needed to advise clients on the new rules.

How fast does your AI tool know?

Most legal AI vendors promise “always up-to-date content.” None of them explain what that means in practice. They don’t tell you how long the gap is between a law being published and becoming searchable. They don’t explain what happens during that gap. They don’t show you who verifies that the ingested text actually reflects what was published.

This silence should concern anyone who relies on these tools for professional advice.

What “always up-to-date” actually requires

Belgium’s Belgisch Staatsblad publishes new legislation daily in both Dutch and French. In 2024 alone, it published a record 141,310 pages — roughly 390 pages per day. Programme laws (programmawetten) land twice per year, each one amending dozens of provisions across unrelated domains in a single legislative act.

This volume makes manual monitoring impossible. But it also makes automated monitoring genuinely difficult. Legal text isn’t web content. It has nested hierarchies — sections, subsections, articles, paragraphs, points — that standard text processing ignores. Amendments use specialised language: “Article 145/1 of the WIB 92 is replaced by the following…” The system needs to understand not just the new text, but which existing provision it replaces, when the change takes effect, and which cross-references are affected.

Standard RAG systems achieve only 58% accuracy on version-sensitive questions because they retrieve semantically similar content without checking temporal validity. Version-aware systems can reach 90% — but this requires dedicated architecture, not just “updating the database” (Huwiler et al., 2025).

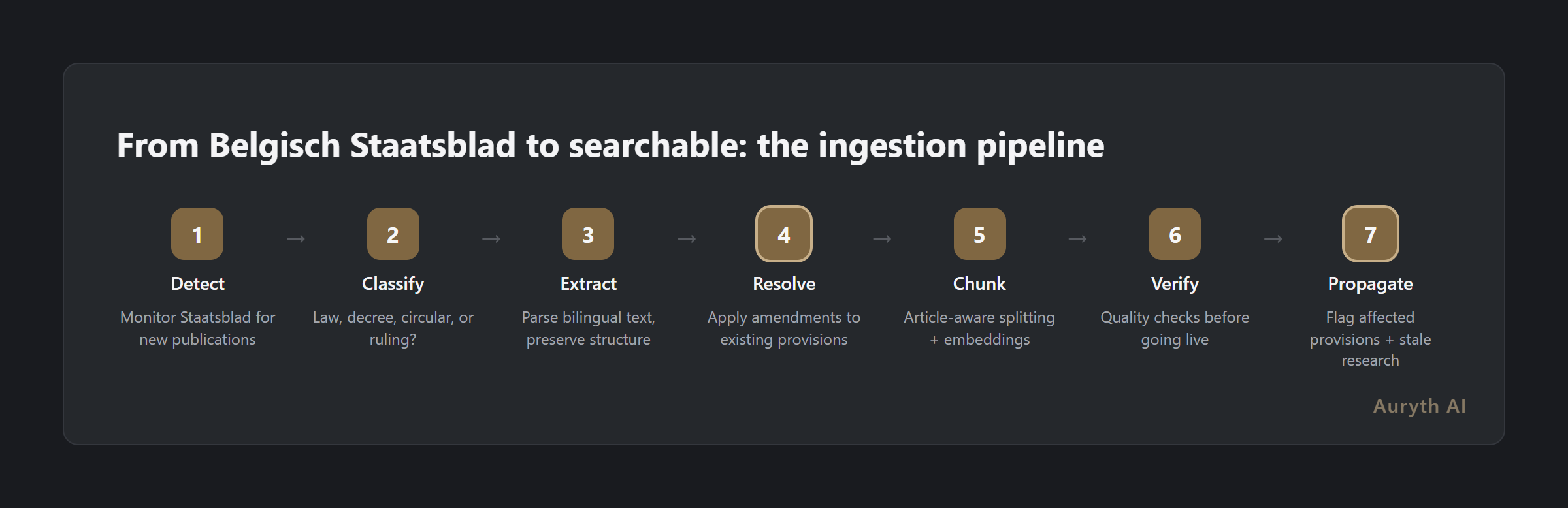

The seven-stage pipeline

Here’s what needs to happen between a law being published and a professional being able to search it:

Stage 1: Detection. A monitoring agent watches the Belgisch Staatsblad for new publications. This runs continuously — not weekly, not daily. New publications are detected within hours of appearing in the official journal.

Stage 2: Classification. Not everything published requires the same treatment. A new federal law, a royal decree, an administrative circular, and a court ruling each have different authority levels, different scopes, and different processing requirements. The system classifies each document by type before processing.

Stage 3: Text extraction. The raw publication is parsed into structured text. This sounds simple until you encounter bilingual formatting, nested article structures, tables of rates, and amendatory language that references provisions in other codes. Both the Dutch and French versions are authoritative — cross-language consistency must be preserved.

Stage 4: Amendment resolution. This is the hardest stage and the one most vendors skip or simplify. When a programme law says “Article 215 of the WIB 92 is amended as follows,” the system must identify the existing provision, apply the amendment, and create a new version while preserving the old one with its validity dates. A single programme law can trigger dozens of these operations across multiple codes.

Stage 5: Chunking and embedding. The processed text is split into semantically meaningful units — not arbitrary paragraphs, but article-aware chunks that preserve legal structure. Each chunk is converted into vector embeddings for semantic search, while the full text is indexed for keyword search. Metadata is attached: entry-into-force date, authority level, jurisdiction, and cross-references.

Stage 6: Verification. Before new content enters the live corpus, it passes through quality checks. Does the parsed text match the published source? Are article numbers correctly extracted? Do cross-references resolve to existing provisions? Are entry-into-force dates accurate? This stage catches parsing errors before they become bad advice.

Stage 7: Impact propagation. The knowledge graph identifies which existing provisions, rulings, and commentary are affected by the change. Saved research citing those provisions is flagged as potentially stale. This is where the system adds value beyond just “containing the new law” — it tells you what else changed because the law changed.

Where it gets hard: the challenges nobody talks about

Amendatory language is ambiguous. “The first paragraph of Article 344 is supplemented by a sentence…” — which sentence? Where exactly? Legal drafting isn’t always precise about insertion points, and automated parsing must handle these ambiguities correctly or not at all.

Implicit amendments are invisible. Some law changes affect the meaning of existing provisions without explicitly amending them. A new EU directive may override domestic law without the domestic text being modified. Research on implicit change detection shows accuracy at only 60% — a genuinely unsolved problem (Huwiler et al., 2025).

Cross-domain cascades are complex. A change to the WIB 92 income tax code may affect how TAK 23 insurance products are taxed, which in turn affects the VCF inheritance tax treatment in Flanders. These cross-domain impacts require knowledge graph reasoning, not just text processing.

Bilingual divergence happens. The Dutch and French versions of Belgian law are both authoritative but not always perfectly aligned. Translation differences occasionally create genuine legal ambiguity — and the system must flag these rather than silently picking one version.

The questions your vendor should answer

If your legal AI tool claims to be “always up-to-date,” ask these five questions:

| Question | Why it matters |

|---|---|

| How quickly after Staatsblad publication is a new law searchable? | Hours? Days? Weeks? The gap is where risk lives |

| How are amendments to existing provisions processed? | Automated? Manual? Both? The method determines accuracy |

| Who verifies that ingested content matches the published source? | Automated checks? Human review? Neither? |

| What happens to saved research when underlying law changes? | Is the user notified? Or do they discover staleness the hard way? |

| What is the error rate of your ingestion pipeline? | If they won’t share this number, ask why |

The absence of answers to these questions is itself an answer.

Common questions

How quickly should a law change be reflected in a legal AI system?

For critical changes — new tax rates, amended deadlines, modified reporting obligations — same-day ingestion is the appropriate standard. For less urgent content like doctrinal commentary or lower-court decisions, 24–48 hours is acceptable. Any system that takes weeks to reflect published law changes is operating on a timeline that creates professional risk.

Can the ingestion pipeline make mistakes?

Yes. Parsing errors, incorrect amendment resolution, missed cross-references, and metadata extraction failures all occur. The question isn’t whether mistakes happen — it’s whether the system detects and corrects them before they reach the professional. This is why the verification stage exists, and why it should never be skipped for speed.

Why does bilingual processing matter for Belgian law?

Both the Dutch and French versions of federal Belgian law are equally authoritative. If a system only ingests one language version, it misses legal content that exists only in the other. More importantly, when the two versions diverge in meaning — which happens — the system should flag this divergence rather than silently serving one interpretation.

Related articles

- What is temporal versioning — and why your legal AI tool probably serves you yesterday’s law → /en/blog/temporele-versionering-juridische-ai-en/

- What is chunking — and why it’s the invisible foundation of legal AI quality → /en/blog/wat-is-chunking-juridische-ai-en/

- What is a knowledge graph — and why it changes how AI navigates Belgian tax law → /en/blog/knowledge-graph-fiscaal-recht-en/

How Auryth TX applies this

Auryth TX runs continuous monitoring of the Belgisch Staatsblad and related official sources. New legislation is detected, classified, and parsed within hours of publication. The pipeline uses article-aware chunking that preserves the hierarchical structure of Belgian legal texts, with amendments resolved against existing provisions to maintain version history.

Every ingested document passes through automated verification before entering the live corpus. The knowledge graph propagates changes to affected provisions, and saved research citing impacted articles is flagged for review. We don’t claim perfect ingestion — we claim transparent ingestion, where errors are caught and corrected rather than hidden.

When Belgian tax law changes tomorrow, our system knows tomorrow. Not next week. Not “eventually.”

Sources: 1. Huwiler, D. et al. (2025). “VersionRAG: Version-Aware Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Evolving Documents.” arXiv preprint. 2. Premasiri, D. et al. (2025). “Survey on legal information extraction: current status and open challenges.” Knowledge and Information Systems, 67, 11287-11358. 3. Ariai, F. & Demartini, G. (2024). “Natural Language Processing for the Legal Domain: A Survey.” ACM Computing Surveys.